“Whole empires would rise and fall on the mix, the bread and the circuses and lifeblood of the contemporary mind; no one could imagine life without it or remember when things were different. But prior to the day when London hit full swing — some time, more or less, in August ‘63 — it hadn’t existed before. Within three miles of Buckingham Palace in a few incredible years, we were all of us born.” 1

I don’t remember what year it was, only the expectant silence and the scratch of worn upholstery on my legs as I perched on the “listening chair” in my father’s music room, which was filled floor-to-ceiling with albums, cassettes and reel-to-reel tapes, carefully organised and alphabetised. I can still see him reaching unerringly up to one of the shelves, and it was clear even to my young eyes that he didn’t need any organisational systems to know exactly what he was reaching for.

I watched as he pulled down an album, slipped the record out and laid it on the turntable. He cleaned the vinyl and set the needle on the edge with a soft pop, then passed the sleeve to me with the reverence of a rabbi handing a young student a Torah scroll.

My father was a music historian and the day he put Sgt. Pepper in my hands, long before I was anywhere near old enough to understand it, he gave me the only inheritance he’d ever pass on to me. He taught me that music was important, and that this music was equal in substance to the bookshelf of classics that filled a wall in the adjoining living room — volumes by Shakespeare and Milton and Whitman and Blake. In our house, there was no difference in stature, between Songs of Innocence and Hard Day’s Night, The Divine Comedy and Revolver, Othello and The White Album. If anything, music, and especially this music, mattered more, which is probably just as well, since I spent far more time in my father’s music room than I did with that library of classic books

It took me a long time to understand the full weight of that moment and of my father’s gift to me. I grew up and, like most of us, became a lot of things — among them, a wordsmith, a storyteller, a songwriter, a mythologist and a student of human behaviour. Through it all, music... this music... was always there, in much the same way it’s there for all of us. Woven into the fabric of who we are, why our world is how it is.

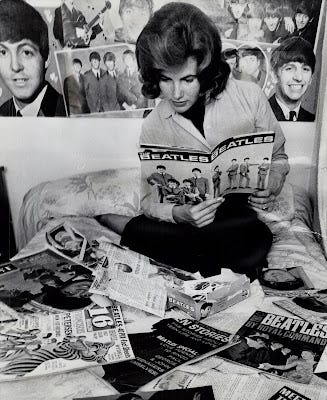

Many, many writers before me have talked about how important the music of The Beatles is, and rightfully so. It's hard to know where we’d be without it. It's hard for me to come up with anything else that would have been powerful enough to crack the old world open and give birth to a new one, the way this music did.

The music of The Beatles — of Lennon & McCartney — is such a stunning artistic achievement that it's easy to miss seeing that the story of how that music was created carries weight of its own, independent of the music that came from it.

It’s a story that’s inextricably intertwined with the shimmering, tumultuous, world-changing decade we call the Sixties. And it’s a story that — in ways we’re mostly not consciously aware of — continues to influence our culture and our lives, as much as the music does, right up into the present day.

Stories matter. We know this already, but it’s worth a reminder that stories are the fundamental organising principle by which we make sense of the chaos of the world. Our personal stories help us make meaning of the events of our lives. Our shared cultural stories are the fabric that binds us together. And our sacred stories give us hope that all of the chaos has some kind of purpose.

The story of The Beatles is both a shared cultural story and — as I’ve come to understand through immersing myself in it over these past years — a sacred story. And for many of us, it’s so deeply woven into our lives that it’s a significant part of our personal stories as well.

“This isn’t show business. This is something else. This is different from anything that anybody imagines. You don’t go on from this. You do this and then you finish.” — John Lennon in 1964 2

When a story is big enough to have a significant, long-term impact on our world, it begins to defy ordinary ways of understanding it and enters into the realm of the mythological. Mythology is really the only means we have of making sense of stories that are too big for the more blunt-edged tools of history and journalism and musicology.

The story of The Beatles, intertwined with the Sixties, is that kind of mythological story.

None of this was yet on my mind in November of 2021, when I, along with most of everybody else with an internet connection, sat down to watch Get Back, Peter Jackson’s six-hour documentary that promised to rewrite the history of the breakup of the band.

Is there an exact moment when a passion... an obsession... flares into being? Somewhere between Mal setting down Ringo’s drum skin on the rainbow-lit Twickenham soundstage and the final notes of the Rooftop Concert, the spark that my father planted when he put Sgt. Pepper in my hand all those years ago ignited and became a wildfire. My life rearranged itself and stayed rearranged, around a soul-deep need to understand this music, and this story, more fully.

I started, of course, with the standard stuff, the books recommended on the lists of “best books about The Beatles,” and when I finished with those, I kept reading. And as I made my way through the canon of Beatles writing, I started to notice something... odd.

The history... the story… doesn’t hold together.

There are, of course, the expected inconsistencies — too many to count — between eyewitnesses and even between the four Beatles, who regularly contradict each other and themselves. That’s situation normal for any biography, but more than that, there are obvious gaps in the timeline, often at key turning points, where no one — not the writers nor the band — have much of anything at all to say. And in even the most “complete” books, there are major fallacies of cause and effect and basic errors of human psychology relative to the people involved. Oddest of all, none of the writers (nor anyone else, including the Fabs) seem to notice or express any concern that the story they’re telling is, upon closer inspection, a scrambled Aeolian clusterfuck of nonsense.

Books piled up on my kitchen table, their margins crowded with scribbled “??!!”s and “wtf?”s. Browser tabs multiplied, pages filled up with notes. It was the second half of the pandemic, and hidden away in my little house in the woods of midcoast Maine, far from the chaos of it all, I had time, especially in winter when the road into town ices up. The more I read, the less the story made sense and the more questions I had.

How did this happen? Hundreds of books, millions of words written about The Beatles over the past sixty years, how is it possible that the story of arguably the most revolutionary music ever created is in such bad shape?

Okay, yes, the people involved did a lot of mind-altering drugs in the ‘60s and accurate recall is not what it ideally would be, but still, presumably the writers weren’t tripping when they did their research and wrote all those books. How is it that no one seems to notice or care how bad a shape the story’s in?

Stories matter and broken stories do damage. When our personal stories fall apart, the fabric of our identity is torn. When our shared stories fall apart, the fabric of our shared cultural identity is torn, and by extension our connection to each other. When our sacred stories fall apart, we lose our ability to fix any of it, because we lose the ability to think bigger than our individual circumstances and everyday lives.

Frustrated, but also increasingly intrigued at the mystery, I levelled up my research. The pile of books on the kitchen table grew taller and more structurally unsound. Other, non-Fab projects were back-burnered, as I read more deeply, searching out even less prominent, even less canonical sources, making more notes, asking more questions.

Spring came, the ice melted and the road cleared. My research took me to Liverpool, London and Hamburg, and then to Liverpool again and then again. I sought out Cavern girls and Quarrymen, spent time in the white-gloved silence of the rare book room at the British Library in London, dug through the archives and tried the patience of the archivists at the Liverpool Central Library and the Museum of Liverpool.

Out of the chaos, a pattern slowly emerged. I began to see that all of the problems with the story are actually a single problem. And that single problem is a lot bigger... and a lot more heartbreaking... than I’d initially thought.

What you’ve just read is the introduction to the main work for which The Abbey was founded — a 20 (ish) -episode3 podcast series, the result of three-plus years of intense research, extreme wear and tear on both my nervous system and the patience of friends and colleagues who (more or less) graciously continue to indulge my single-minded obsession with this extraordinary story and its mysteries.

The first half of the series offers my answers to the questions posed in the introduction — how and why the story of The Beatles is in such appalling disrepair, why this disrepair matters far more than one might think, what can be done to mend the story and why mending it is a matter of some urgency.

The second half, inspired by the brilliant second season of Cocaine & Rhinestones, will attempt the high-wire act of re-telling the story of The Beatles in a way that I’ve come to believe is more accurate, more complete, and — to me, at least — more beautiful and profound than the story as it’s currently told.

Right now, I’m in the midst of writing the first half, and that’s going to take a few more months to wrap up. While this is happening, The Abbey likely won’t be updated with anything new, as this madness completely reasonable project is demanding all of my focus.

This is intense, careful, deliberate work, as is everything I write for The Abbey, only more so. Stories matter and one of the goals of this series is to show in detail why the story of The Beatles matters more than most. And I feel called to do the healing work of handling this story with the full measure of my care and attention, given its importance and its fragility.

This quest that I’ve set out on is more than a little intimidating in its scope, so I appreciate your patience. I’ll do all I can to make it worth the wait.

If you have a friend who might be interested in this series, now is a great time to invite them to subscribe. (the “Yesterday” piece is a good gateway drug 😎) I’m hoping this series will be of interest not just to “Beatle people,” but to people interested in culture, music, mythology, psychology, storytelling, spirituality, and most of all, unexpected possibilities… and hope… for healing our broken world.

Thank you, every one of you, for reading and sharing The Abbey. I’ll see you in a few months. Meanwhile, I invite you to come along on the often nerve-wracking but always adventurous journey of writing this series, which I share on my personal substack, The Red Abbess.

Warmest,

Faith

Ready Steady Go: The Smashing Rise and Giddy Fall of Swinging London, Shawn Levy, 2002

quoted in Love Me Do! The Beatles' Progress, Michael Braun, 1995

Final episode total subject to change according to the vaguaries of the creative process.