Hi everyone,

Periodically in my research, I come across people expressing surprise that none of The Beatles could read or write music. These comments usually include some mention of how extraordinary it is that The Beatles could have revolutionised pop music without this ability.

Even Paul McCartney sometimes seems a little caught up in this amazement. Here he is in The Lyrics:

One of the things I always thought was the secret of The Beatles was that our music was self-taught. We were never consciously thinking of what we were doing. Anything we did came naturally. A breathtaking chord change wouldn’t happen because we knew how that chord related to another chord. We weren’t able to read music or write it down, so we just made it up. My dad was exactly the same. And there’s a certain joy that comes into your stuff if you didn’t mean it, if you didn’t try to make it happen and it happens of its own accord. There’s a certain magic about that. So much of what we did came from a deep sense of wonder rather than study. We didn’t really study music at all.

Paul is right that not knowing the rules can make it easier to be creatively innovative. And without question, what The Beatles accomplished in the studio is unique and extraordinary. But their ability to create their music without knowing how to read/write music is not extraordinary, nor did this lack of knowledge make The Beatles in any way unique.

So this week, I thought maybe I’d do my part to debunk this widespread misperception.

⚠️A few caveats before we begin—

First, this is, as usual, very scruffy.

Second, an apology to my fellow songwriter/musician friends: in the interests of not getting into the weeds, this is about to get very imprecise and over-generalized. Please forgive the many errors of nuance.

Third, an apology to those of you who are not musicians but who nonetheless Know All Of This Already, Geesh, Faith. Given the number of times I’ve heard or read the “gasp! They didn’t read music! How did they manage?” it’s pretty clear that many people are not familiar with the basics of how a song is written, arranged and recorded. So I’m going to be super-basic here and assume nothing. If you already know all of this, just skip to the end and enjoy Paul’s very McCartney-esque arrangement chart.

Okay, so then.

When people say The Beatles didn’t read or write music, what they mean is that none of the four could read/write formal musical notation. In Western culture, that notation looks like this—

The musicians who most need to know how to read/write formal notation are, of course, classical musicians — and especially classical musicians who play in an orchestra or other ensemble. And because classical musicians rely on this kind of notation, composers who write for classical musicians need to write their music in formal notation, if they want anyone to be able to actually play it.

So for example, when Paul was commissioned to write Liverpool Oratorio, he relied on classical conductor/composer Carl Davis to translate his work into formal musical notation for the musicians and singers who performed it.1

Most famously, Beatles producer George Martin — also a classically trained musician — frequently translated Lennon/McCartney’s musical ideas into formal notation for the classical musicians who sometimes played on their songs.

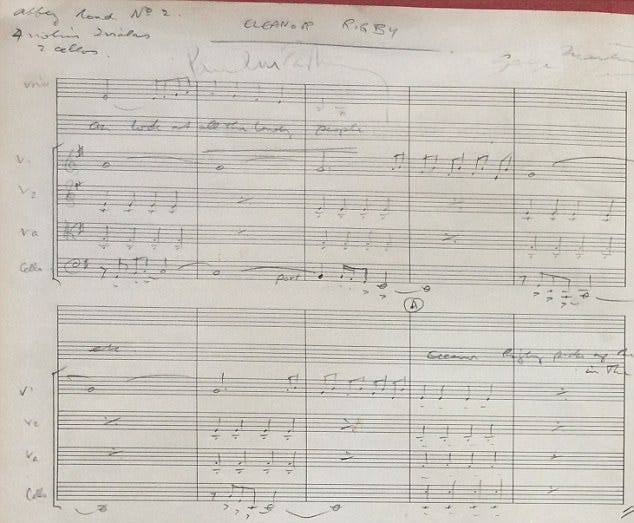

Here’s a bit of George Martin’s score for “Eleanor Rigby”—

George Martin had to write out the score this way because, again, classical musicians are trained to play using explicit and very precise instructions, as is evidenced in George Martin’s account of talking with John and Paul about the orchestral break in “A Day In The Life”—

John said: “What I’d like to hear is a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world. I’d like it to be from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, not only in volume, but also for the sound to expand as well. I’d like to use a symphony orchestra for it. Tell you what, George, you book a symphony orchestra, and we’ll get them in a studio and tell them what to do.”

“Come on, John,” I said, “there’s no way you can get a symphony orchestra sitting around and say to them, ‘Look, fellers, this is what you’re going to do.’ Because you won’t get them to do what you want them to do. You’ve got to write something down for them.”

“Why?” asked John, with his typically wide-eyed approach to such matters.

“Because they’re all playing different instruments, and unless you’ve got time to go round each of them individually and see exactly what they do, it just won’t work.’”

George Martin continues his story with—

I marked the music ‘pianissimo’ at the beginning and’fortissimo’ at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible, almost inaudibly, and end in a (metaphorically) lung-bursting tumult. And in addition to this extraordinary piece of musical gymnastics, I told them that they were to disobey the most fundamental rule of the orchestra. They were not to listen to their neighbours. A well-schooled orchestra plays, ideally, like one man, following the leader. I emphasised that this was exactly what they must not do. I told them ‘I want everyone to be individual. It’s every man for himself. Don’t listen to the fellow next to you. If he’s a third away from you, and you think he’s going too fast, let him go. Just do your own slide up, your own way.’ Needless to say, they were amazed. They had certainly never been told that before.2

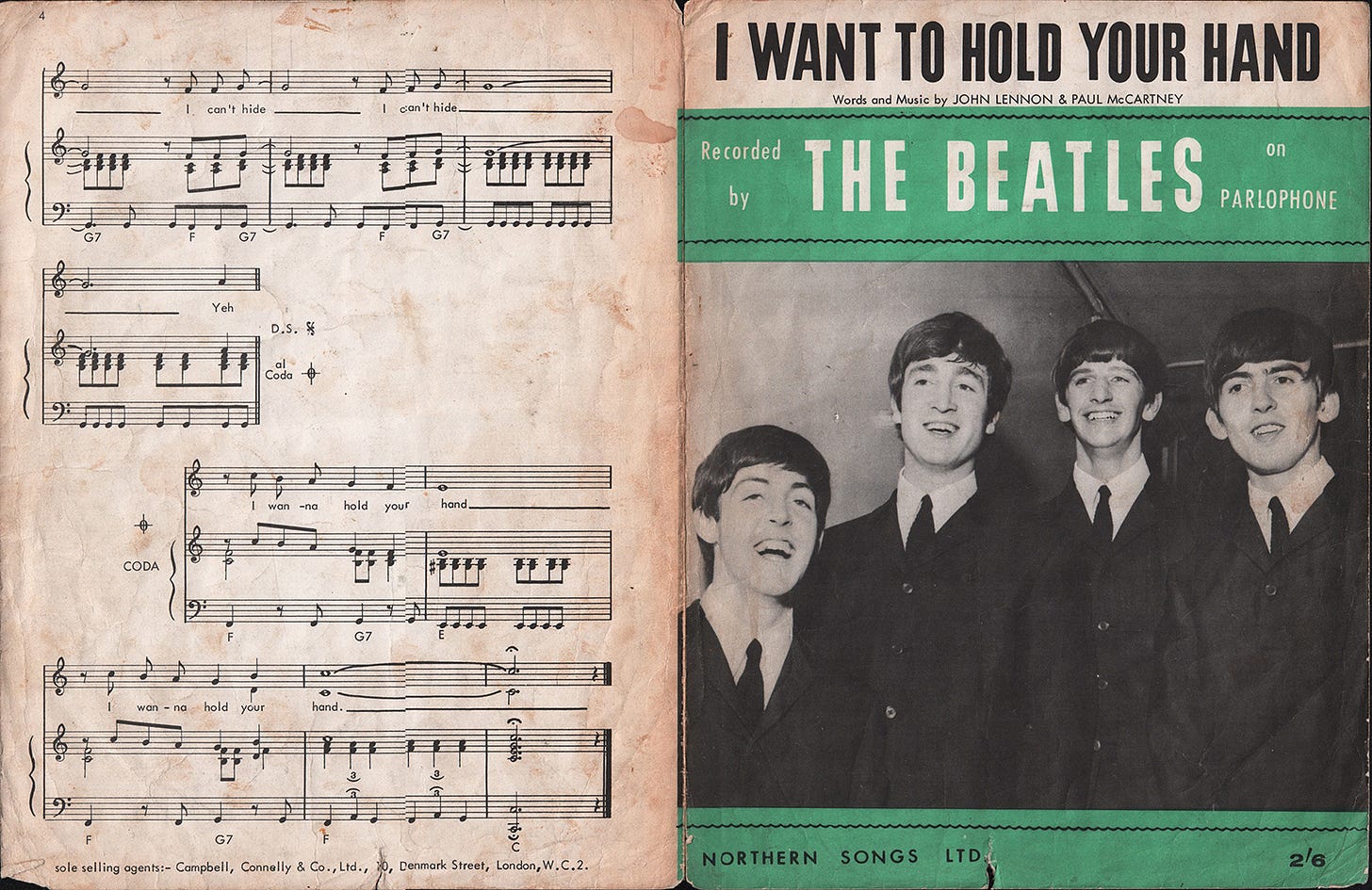

Knowing formal musical notation also used to matter for non-classical songwriters and also for amateur musicians. Before the invention of radio and recorded music, the only way most people could hear popular songs was to get the sheet music and learn to play the song at home on whatever instrument they had — usually a piano. Buying the sheet music for a song was essentially the first-gen version of buying a 45-single — or today, buying and downloading a single song from Apple Music. If you didn’t know how to read sheet music and couldn’t play by ear, you didn’t get to hear the song unless someone else played it for you.

This convention of releasing the formal sheet music for a song continued well past the invention of recording technology and into the 1960s (and maybe even into today, I haven’t kept up). Beatles singles were, for example, routinely released as sheet music—

There are a few reasons why folk, blues, country, pop and rock artists have never, as a general rule, known how to read/write formal music notation.

First, formal musical notation is generally taught as part of formal musical training — either at a music school or through private lessons. That training is expensive and takes many, many years of dedication, usually beginning very early in life. That means the opportunity to learn formal notation isn’t and never has been available to the vast majority of the aspiring musicians who just want to buy a guitar, start a band and play at the local bar or dance hall.

And even if formal training was available, most popular musicians don’t have the temperament for that kind of strict musical education, hence the many stories of famous musicians, including Paul McCartney, who started to take lessons and quickly lost interest in the strict formality of the learning process.

In short, mastering popular music simply doesn’t require learning to read/write formal music notation — not because popular music is any less sophisticated or important as an art form (The Beatles proved that), but because popular music (like jazz) relies on a looser and more spontaneous creative process that’s in many ways antithetical to the more regimented process of learning formal notation.

Formal musical notation — even if the musicians could read it — would be much too bulky and inflexible to work for the more informal and fluid process of arranging and recording a pop song.

All that’s needed to begin recording a pop song is the melody, lyrics and a chord progression. Once these elements are roughly in place, the song is considered finished. And all three of these elements can be easily communicated simply by playing the song as a “demo” using just a single instrument — usually a guitar or a piano — to demonstrate to the rest of the band and the producer how the song goes.

So for example, here’s John’s demo for “She Said She Said”—

The individual parts — guitar solos, vocal harmonies, etc. — are then usually added not as pre-written parts, but in real-time as the arrangement develops during the recording process. And at the same time, the lyrics, melody and chords often evolve, too, as the band “works the song” in the studio.

This real-time evolution of a song is what we hear on those sumptuous studio outtakes that we get on Super Deluxe Beatles remixes. It’s why those outtakes are interesting and valuable for understanding The Beatles creative process.

Here’s the original arrangement for “Got To Get You Into My Life”—

After a bit more work (or maybe a lot more work), here’s the second arrangement—

Paul could have asked George Martin to write out a full formal musical score for “Got To Get You Into My Life” in advance of the session. But even if The Beatles could have read such a score, there wouldn’t have been any reason to. Since the musical arrangement shifted continuously from take to take as the band worked the song, Martin would have had to continually revise the written score to reflect the changes to the arrangement as it developed. That’s not a good use of time on a pop recording session, even on the rare occasions when the musicians do read formal musical notation.

Classical music doesn’t evolve in this same fluid way when it’s being recorded. Classically-trained musicians expect every note of the music to be fully scored by the time they arrive in the studio. This is why there are stories of classical musicians on Beatles sessions becoming disoriented and occasionally even annoyed when there wasn’t a written score ready for them, and when instead Paul composed something on the spot and expected them to play it. In those situations, George Martin wrote out a score right there in the studio as he listened to what Paul was playing.

For example, here’s George Martin talking about recording the piccolo trumpet on “Penny Lane”—

We had no music prepared. We just knew that we wanted little piping interjections. We had had experience of professional musicians saying: ‘If the Beatles were real musicians, they’d know what they wanted us to play before we came into the studio.’ Happily, David Mason [the piccolo trumpet player] wasn’t like that at all. By then the Beatles were very big news anyway, and I think he was intrigued to be playing on one of their records, quite apart from being well paid for his trouble. As we came to each little section where we wanted the sound, Paul would think up the notes he wanted, and I would write them down for David. The result was unique, something that had never been done in rock music before, and it gave “Penny Lane” a very distinct character.3

All of that said, though — and since we’re talking about all of this anyway — there is nonetheless a need for some kind of musical notation on a pop session, if only so the musicians don’t have to rely on memory. And studio session players — aka “hired guns” — in particular need a way to quickly grasp the structure and chord progressions of a song they may only play on a single session before moving on to the next gig.

There are many variations of informal musical notation that pop musicians use when working a studio session. The most common is a simple “lead sheet,” which is just the song lyrics with the chords written above them.

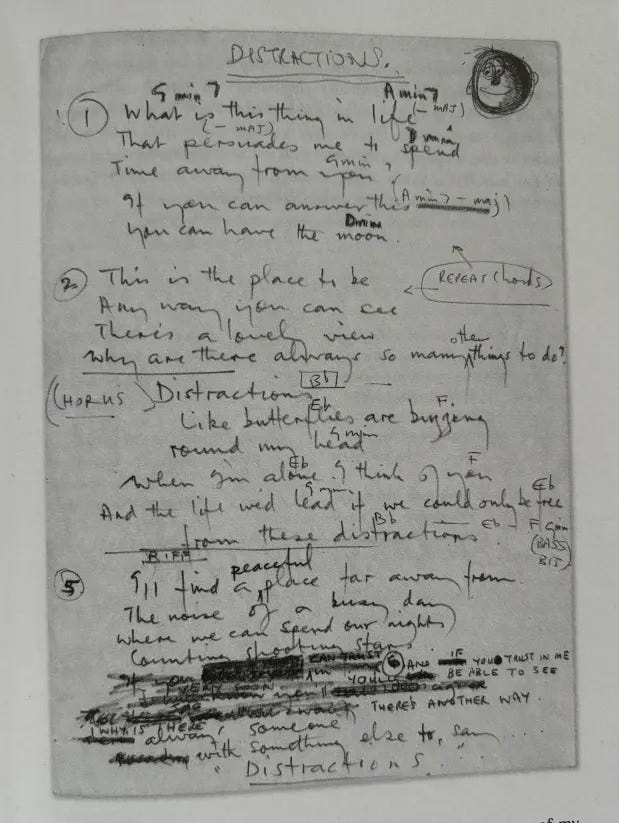

Extant Beatles lead sheets are scarce, because they were seen as disposable and tossed in the trash at the end of the session. 🫢 But here’s one of Paul’s lead sheets from Flowers In The Dirt—

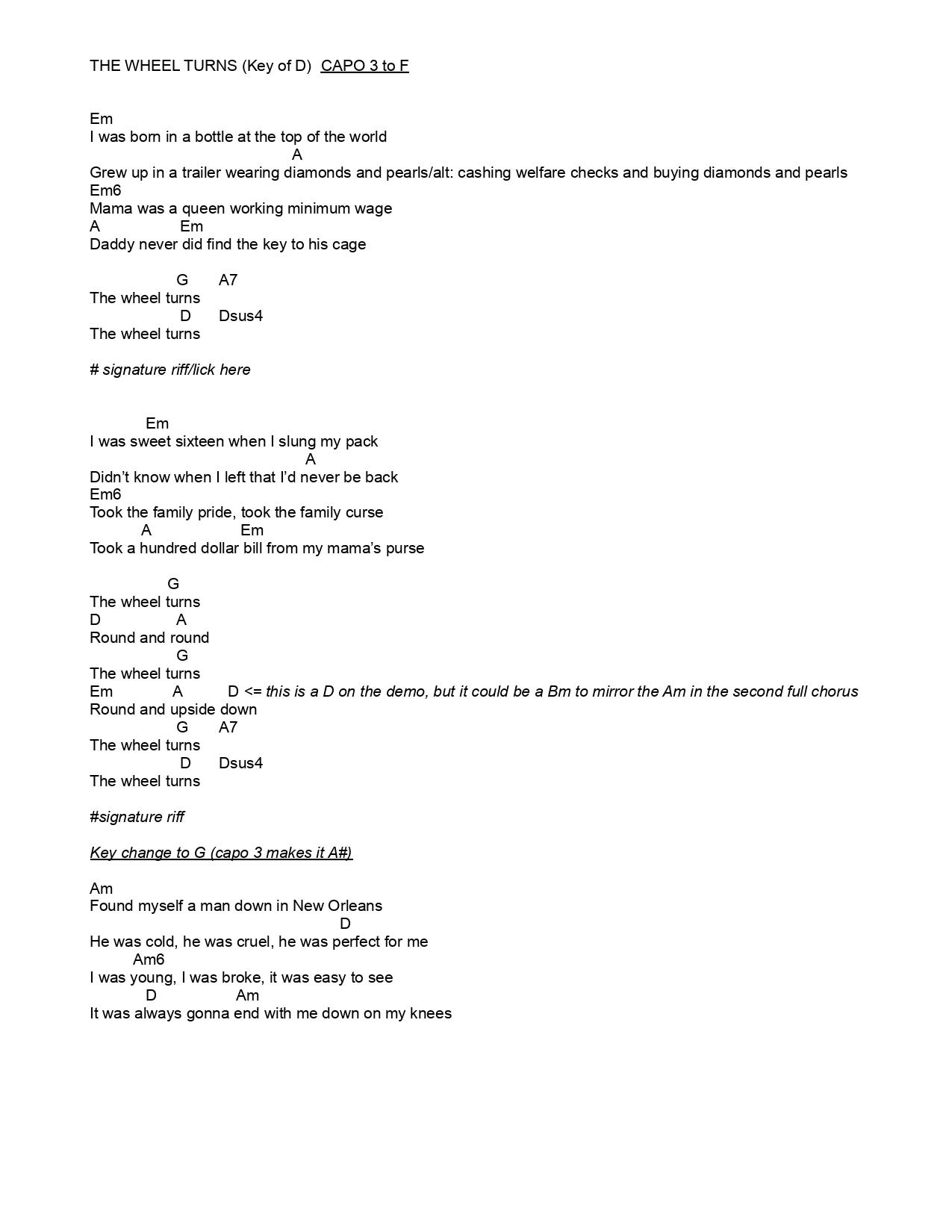

And since that’s a little hard to decipher, here’s one of my lead sheets, from the album that I haven’t finished because I fell in love with Lennon/McCartney and wrote Beautiful Possibility instead—

As you can see, there’s a lot of flexibility in how a song is notated on a lead sheet — songwriters and musicians tend to develop a style that suits their individual needs.

Sometimes, though, musical notation gets standardized. The most famous (and, imo, the most flexible and useful) of these standardized systems of notation is probably the The Nashville Number System, or NNS for short, which is used mostly in (obviously) country music.

Here’s an NNS sheet from my days as a Nashville singer/songwriter, complete with the doodles and notes from an obviously very bored bass player… (I can’t blame him, it was a very boring song)—

Those of you familiar with music theory probably see right away why the Nashville Number System caught on. Instead of writing the “alphabet” chords of the song (A, Bb, C#, etc.), the NNS uses what’s called the “scale degrees” — numbers that denote the position of the chord relative to the root note (hence the name Nashville Number System).

Again, if you’re not familiar with music theory, the details of this won’t make sense, and they don’t need to. The important thing to know about the appeal of the NNS is that not only is it an efficient way to communicate the structure of a song in a setting in which time is money, it also allows musicians to instantly transpose a song to a new key without having to rewrite the lead sheet.

The origin of the Nashville Number System is disputed. For sure it was around before The Beatles began recording — Elvis’ band was known to use it. But since the Nashville Number System was (and I think still is) only used in country music, The Fabs almost certainly didn’t use it. That said, they would have picked it up very quickly had they been exposed to it, because it requires only a very basic understanding of music theory that virtually all musicians develop almost right from the start. And The Beatles certainly would have understood the theory behind the Nashville Number System by the time they arrived at EMI.

All of this is to say that the way in which The Beatles notated their songs wasn’t especially unique or unusual — unless maybe we count the artwork and doodles they drew in the margins. The Beatles’ inability to read/write music wasn’t unique or unusual, either. And Paul is right that if they had known how to read/write formal musical notation, it would almost certainly have stifled the spontaneity of their creative process.

But it’s not quite that simple, either. Because without George Martin’s knowledge of formal musical notation, The Beatles wouldn’t be The Beatles. It’s one of the most important instances of “Beatle magick” that they failed their Decca audition and ended up with a classically-trained producer.

We all benefit from that, because without George Martin’s classical background, it’s unlikely the Fabs would have pushed the boundaries of pop music into what became baroque pop, with songs that included classical elements — songs like “Eleanor Rigby,” “Norwegian Wood,” “She’s Leaving Home,” “Yesterday,” and of course, “A Day in The Life.”

Until next week.

Peace, love, and strawberry fields,

Faith 🍓

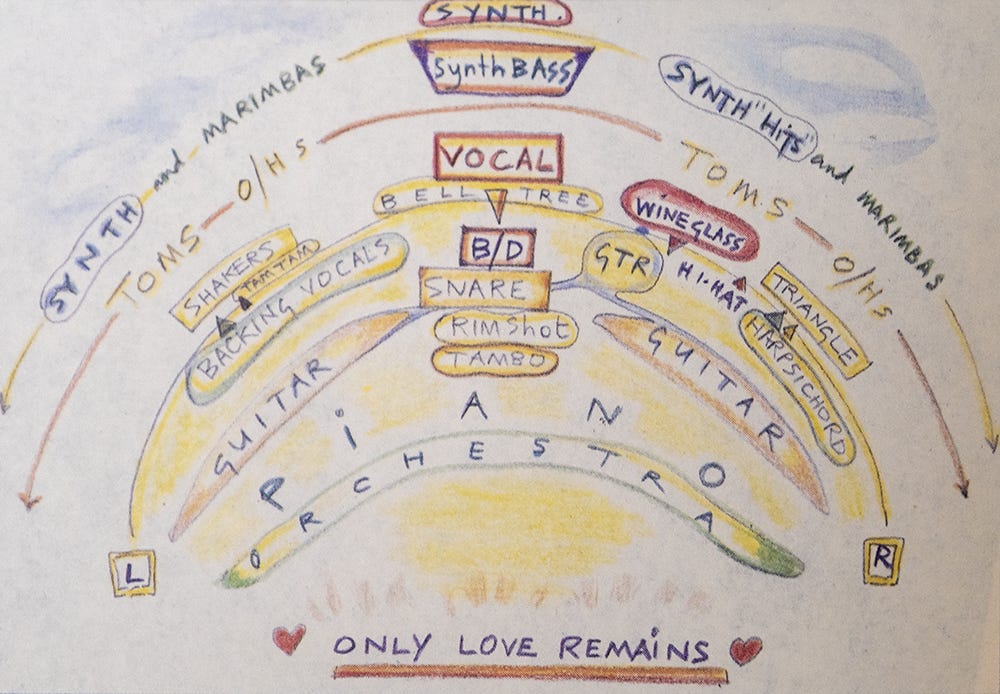

PS — It’s not strictly a lead sheet, but I keep hoping Paul will release a collection of his studio arrangement charts as a book or a series of art prints. Here’s one—

The Making of Liverpool Oratorio is an excellent documentary that shows Paul and Carl Davis engaged in the process of translating Paul’s real-time composition into formal notation.

George Martin (with William Pearson), With A Little Help From My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper, Little Brown, 1994.

George Martin (with Jeremy Hornsby), All You Need Is Ears. St. Martin’s, 1979.