Hi everyone,

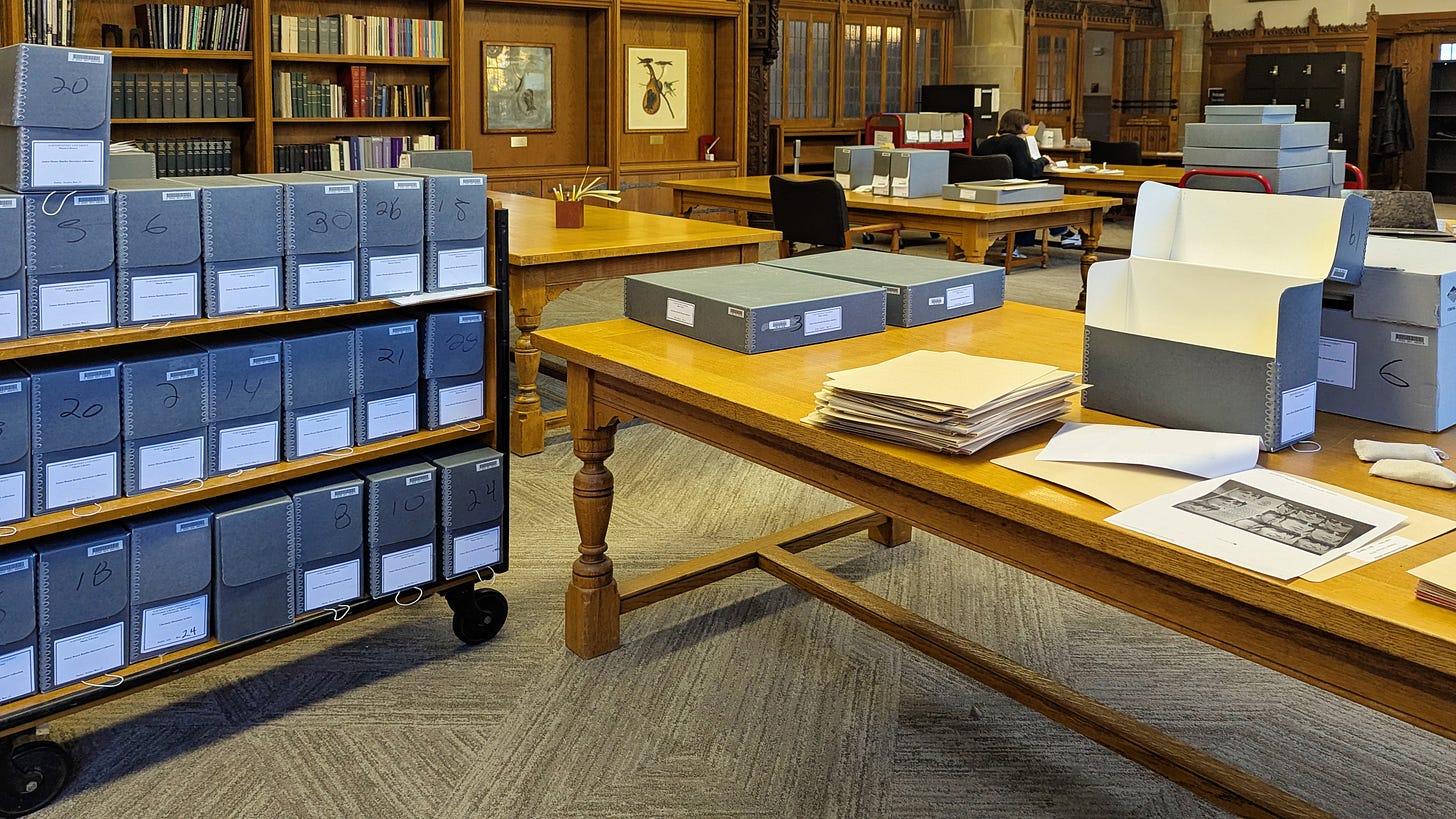

As part of the research for Part Two of Beautiful Possibility, I’ve had the pleasure of spending this past week in the archives at Northwestern University. It was an intense week and I’m a little bit tired, and so this update will be scruffier than usual.

The Northwestern University Beatles collection contains 81 boxes of material, much of which is difficult to find elsewhere. It includes out-of-print articles published between 1963 through 2015, unpublished interview notes and transcripts, personal correspondence, and an extensive collection of auction catalogs.1

As we talked about in Part One of Beautiful Possibility, we’re in an awkward growth stage when it comes to writing about The Beatles. Over the past sixty years, our experience of all things Fab has evolved from a story about “a band that made it very very big, that’s all” into what we’re just starting to recognise (albeit mostly subconsciously) as the foundational mythological story of modern culture (see episode 1:1).

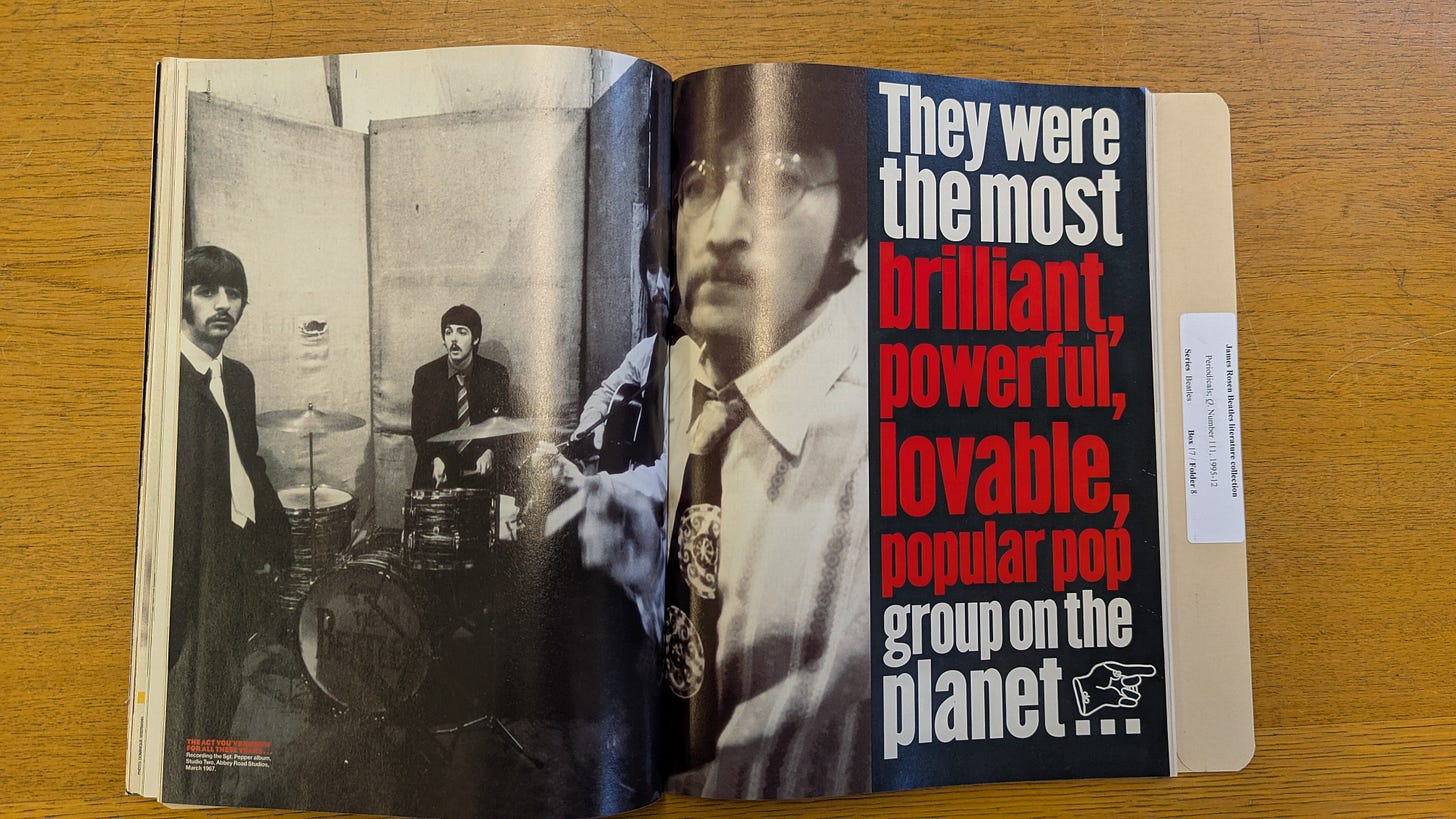

It’s more or less grown from this—

into this—

The growing pains are that this evolution is happening so fast that we’re still in the collective habit of treating this story — this foundational mythology of our modern world — as a pop culture “fandom,” rather than as a subject of serious scholarship more akin to the study of Shakespeare. And the perception of The Beatles as a “fandom” means that a significant amount of primary research material is currently in the hands of private collectors.

All of which brings us back to the Northwestern archive — because archives like the one at Northwestern are a key part of preserving material that would otherwise be sold to collectors and out of reach of scholars.

As this story continues to evolve into something more like the study of Shakespeare, what’s needed is something akin to the Folger Shakespeare Library — a space, physical and virtual, that holds a substantial collection of extant materials related to The Beatles — where scholars can study this story that continues to shape each and every single one of our lives.

Assuming we don’t blow everything up before then, I’m confident that library will exist someday — the existence of the Northwestern collection is an early signal of that. I believe and hope that future generations who recognise more wisely than we do the importance of this story will have access to the full scope of extant primary source material, not just the parts not in the hands of private collectors.

Until then, after a week-long blur of text and paper and images, I left Chicago with 8,533 photographs of archive material. It will, obviously, take a while to go through all of that material. For now, I thought I’d share with you a few things that caught my eye as they flew by.

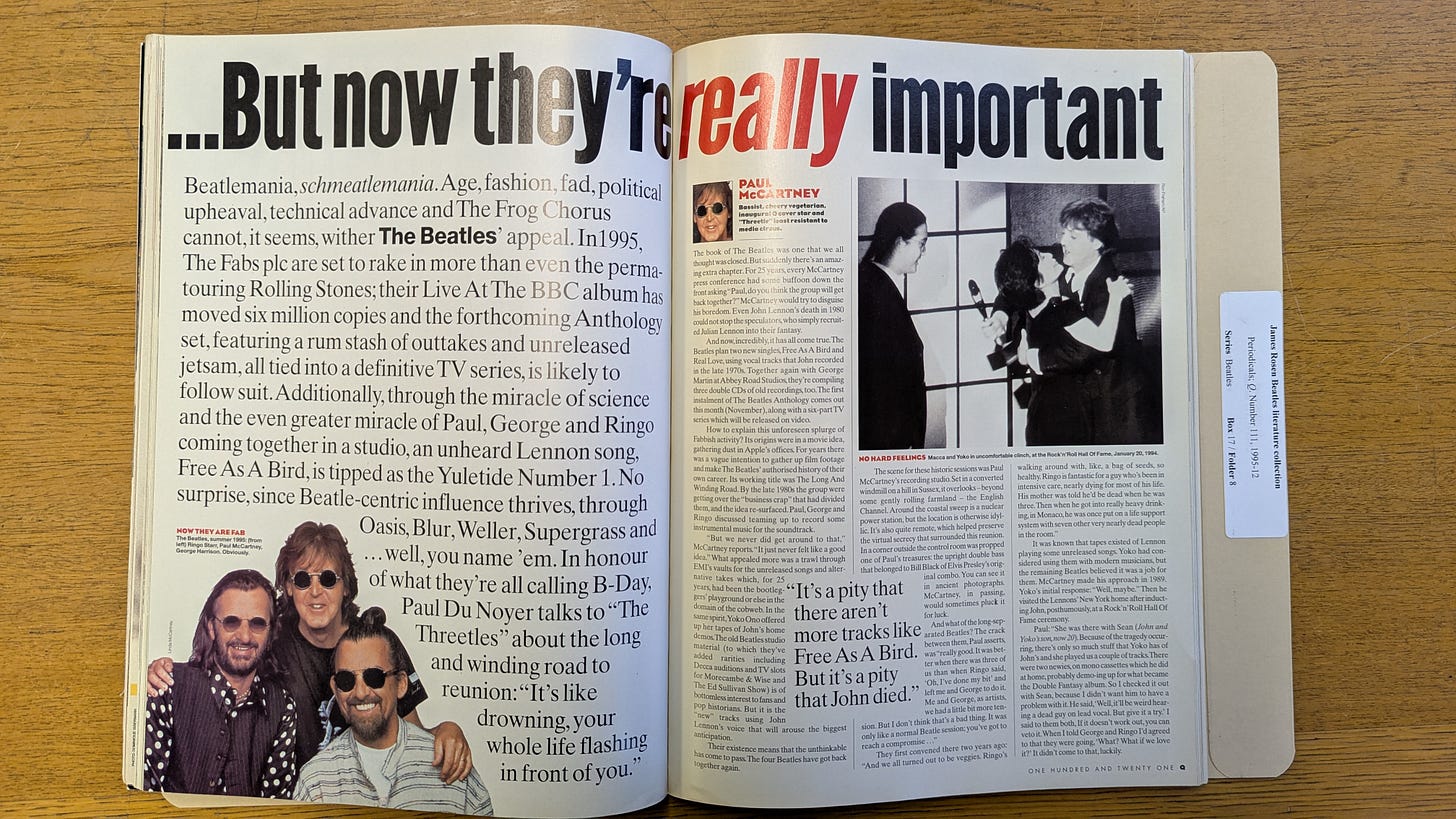

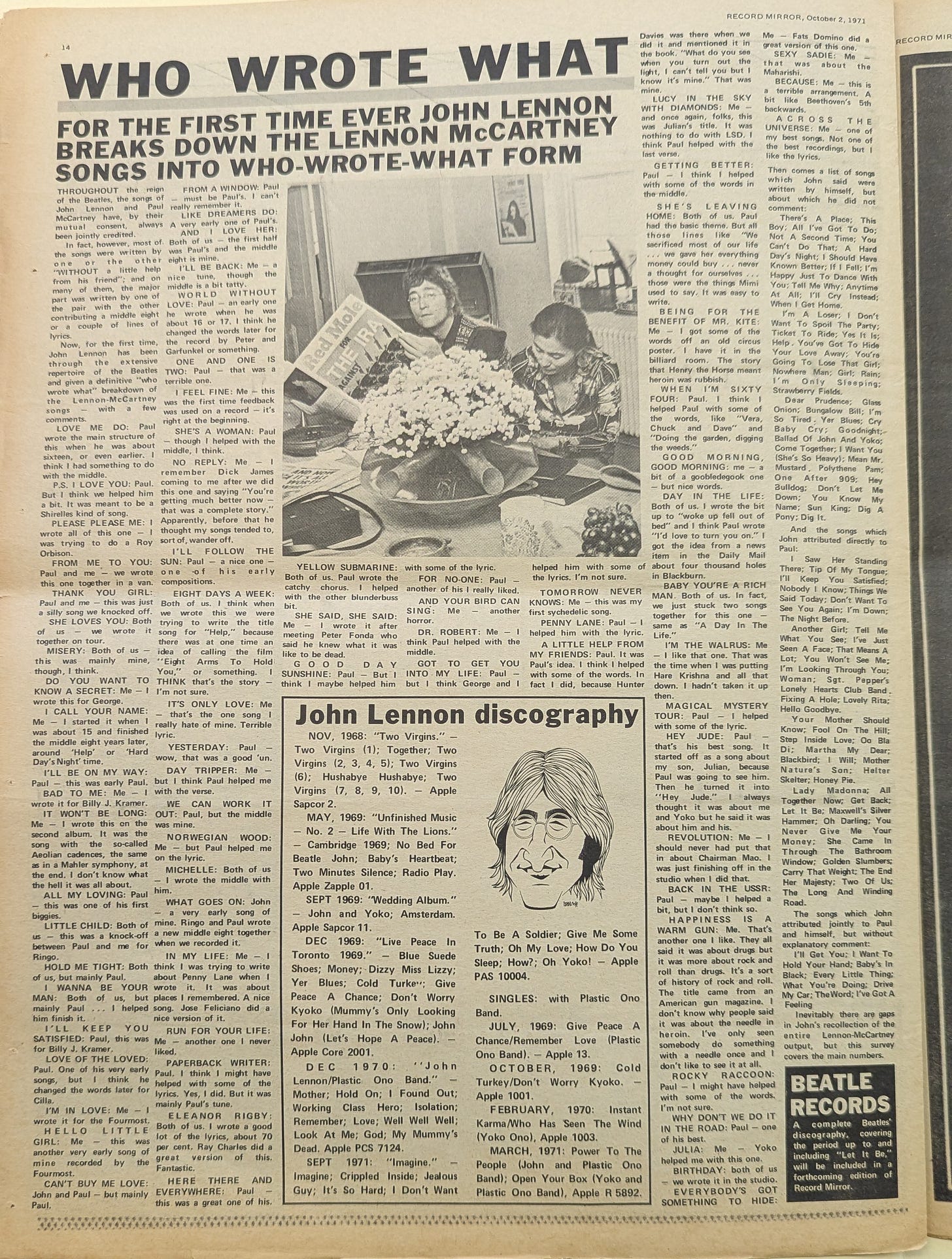

To start with, there’s this less-than-lovely 1971 Record Mirror article—

In Part One of Beautiful Possibility, we stepped through the fallout from John’s claim in a 1971 Rolling Stone interview that his partnership with Paul ended in 1962 — a claim that John retracted literally as soon as he said it and multiple times thereafter. And we also talked about how the division of Lennon/McCartney into “John songs” and “Paul songs” distorted the story from “John and Paul” to “John vs Paul” — from partnership, collaboration and love into “might makes right” competitiveness, rivalry and battle.

There are a few things to notice about this 1971 article, relative to all of that.

First, you might notice that the first paragraph of the article explicitly and unquestioningly anoints this shift from “John and Paul” to “John vs. Paul” as the new gospel truth.

Second, notice that this article is from October 1971 — two months before John’s Rolling Stone interview and nine years before his “who wrote what” 1980 Playboy interview, both of which we talked about in Part One.

That makes this article the earliest (so far) explicit example of the “who wrote what” John vs Paul split, which became the Fisher King wounding at the heart of the story that shapes our world.

(While we’re here, I’ll mention the Rabbit Hole on the “entangled form” of Lennon/McCartney, which proposes that every song John and Paul have written, together and solo, is in a very real way a Lennon/McCartney song, regardless of “who wrote what.”)

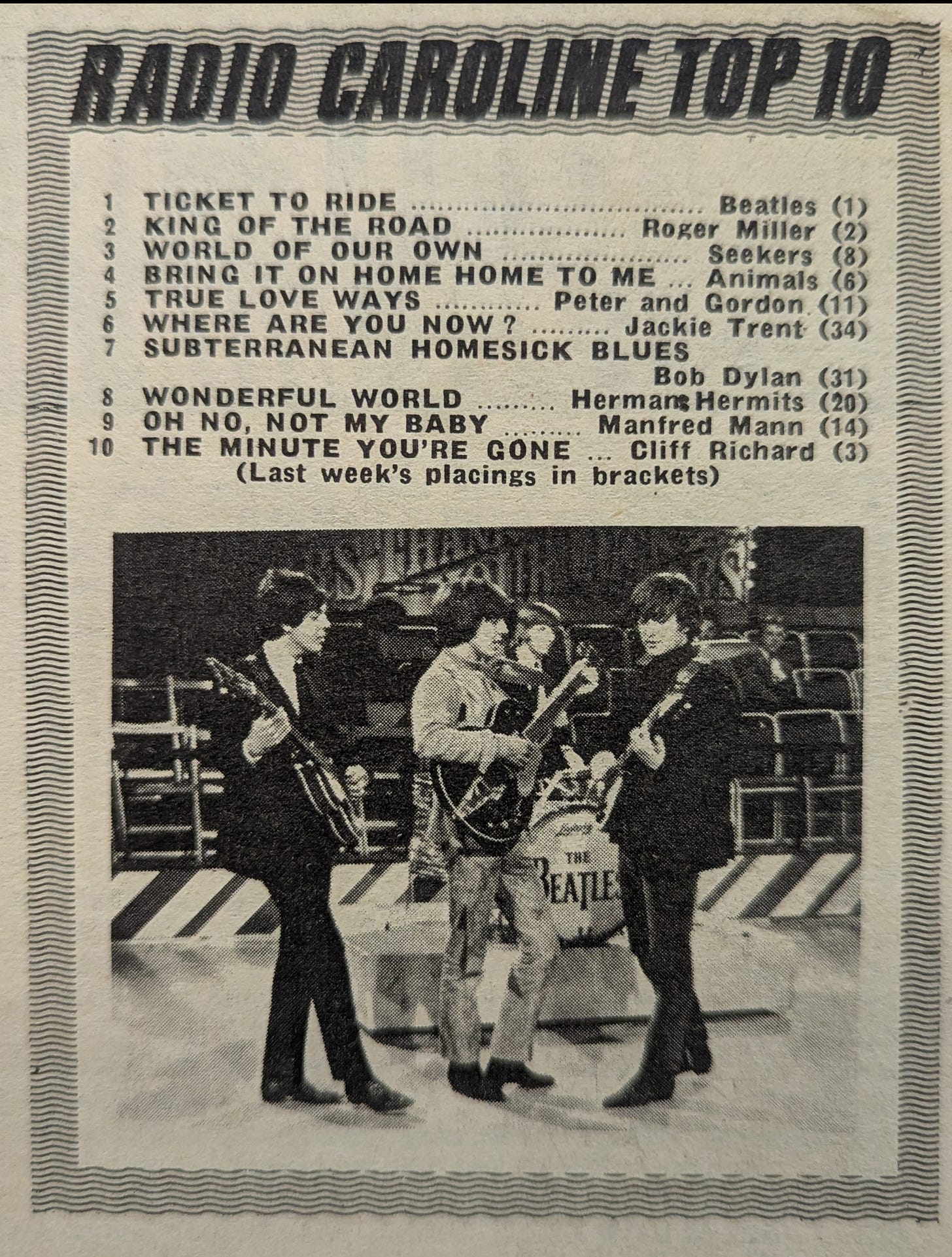

In happier news, another piece that caught my eye was this listing of chart positions in a 1965 issue of the London-based magazine, Music Echo—

As you may already know, this is no ordinary radio station chart listing.

From 1964 to 1968, Radio Caroline was the most famous notorious of the pirate radio stations that broadcast from ships anchored off the coast of Britain in international waters. They did so in defiance of — among other things — the BBC’s aggressive censorship of “inappropriate” lyrics.

This last bit is why this listing especially caught my attention, because “Ticket to Ride” is at #1. The BBC banned “Ticket to Ride” because the line she said that living with me was bringing her down described two lovers living together outside of society’s constraints. I find it deliciously seditious — a pirate radio station advertising a #1 Beatles song banned by the BBC in an advertisement in a mainstream London newspaper. This is the sort of thing that — over and above The Beatles/John and Paul themselves — makes me love this story so much.

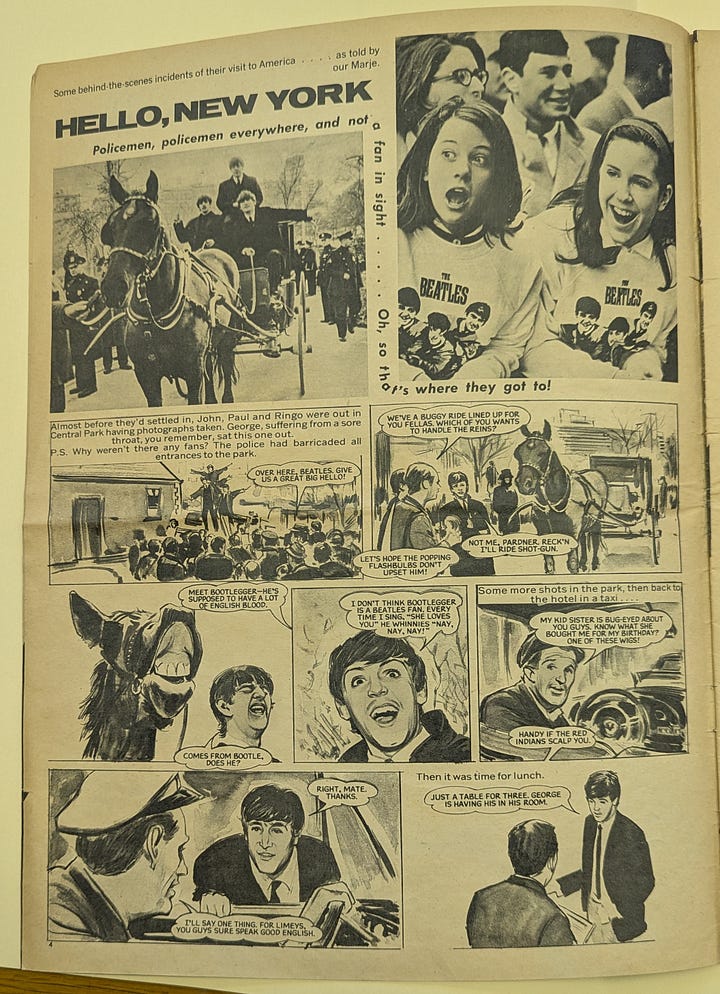

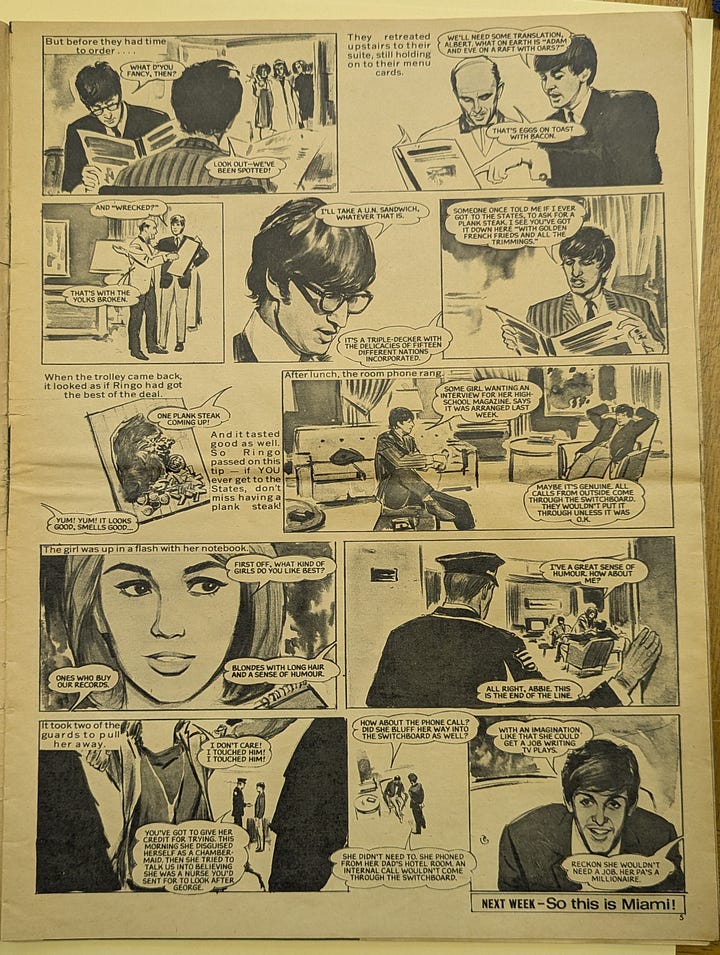

Then there’s this comic, from The Beatles’ 1964 American tour—

NOTE: Click on each image to expand each page out.

Comics like this weren’t unusual in 1964 — this is one of several Beatles comics that I found in fan magazines of the time. Before the Fabs led the way in transforming virtually everything about popular culture, comics (often romantic in theme) were common for the pop stars of the day. 2

When The Beatles made their astounding, seemingly-overnight leap from their “mop top” era into their high psychedelic period, a lot of the younger kids who read the comics were (temporarily) left behind. Artists usually mature at the same rate as their audiences, but during the ‘60s, when The Beatles were essentially reinventing pop music — and thus the culture — every six months, most of their original audience struggled to keep up with the speed of their creative evolution.3

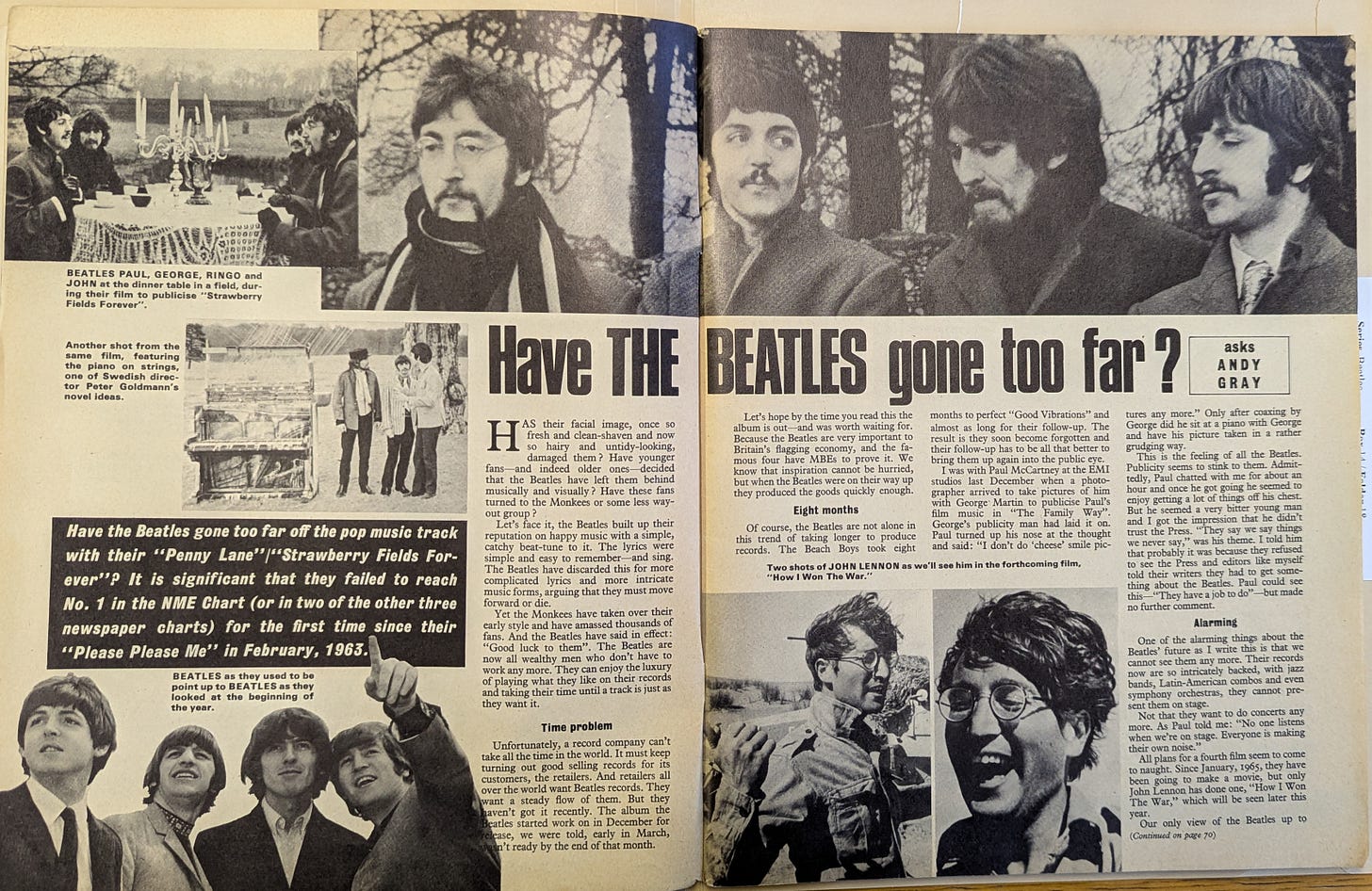

This disorienting shift was both lamented and defended in the teen magazines of the time—

And debated in the fledgling serious music press—

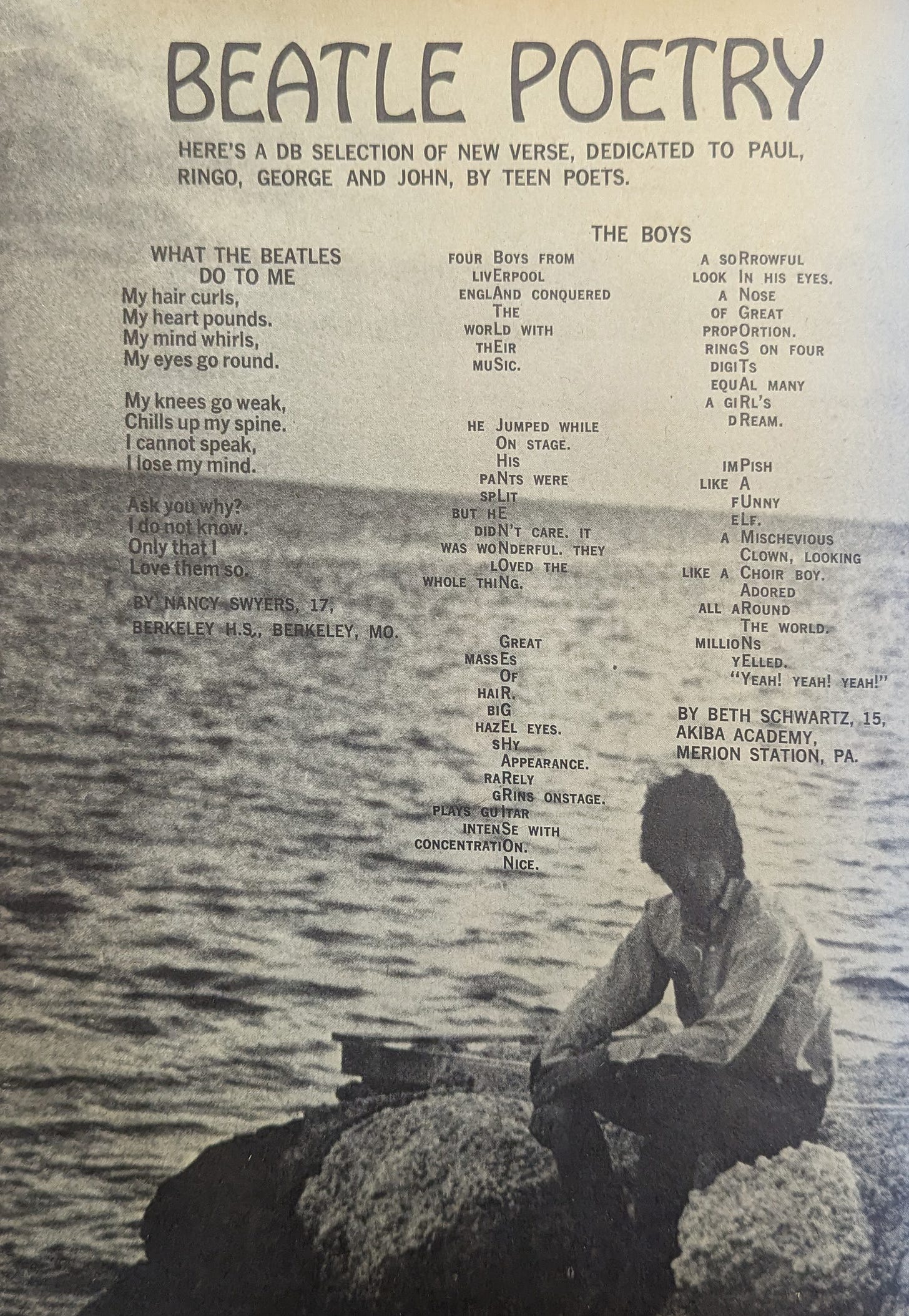

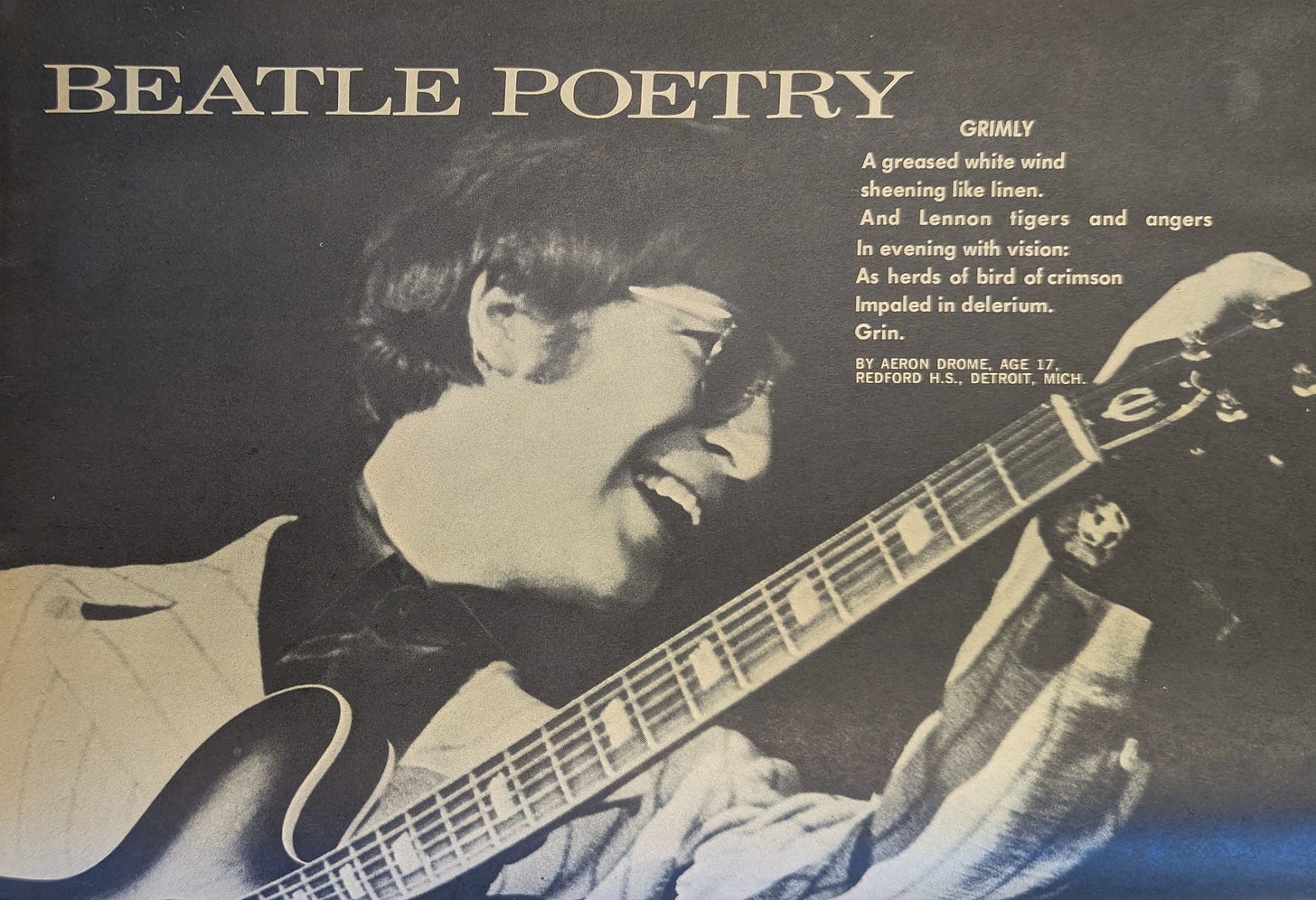

One indication that what was happening with Beatlemania was unique in both its character and intensity is the appearance of Beatle poetry in fan and music magazines—

Unlike the comics, Beatle poetry in fan magazines was unusual, and even more so because the regular poetry feature seems to have been reserved exclusively for The Beatles, at least during the 1960s. The inclusion of Beatles poetry as a regular feature is also a sign of the evolution of pop music into a substantive art form inspiring other art forms, which — as we talked about in Part One of Beautiful Possibility — is what mythological stories tend to do especially well.

And finally…

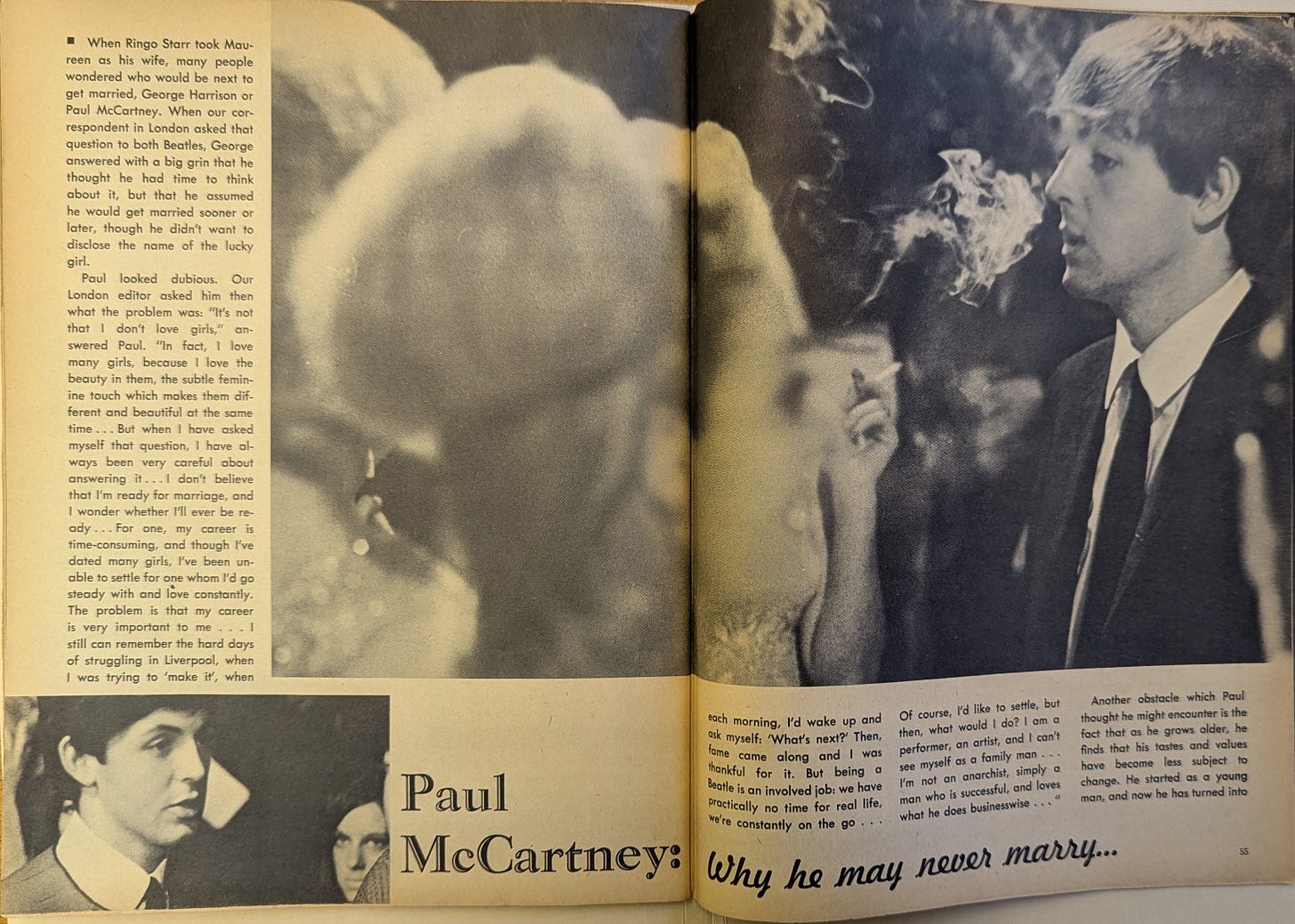

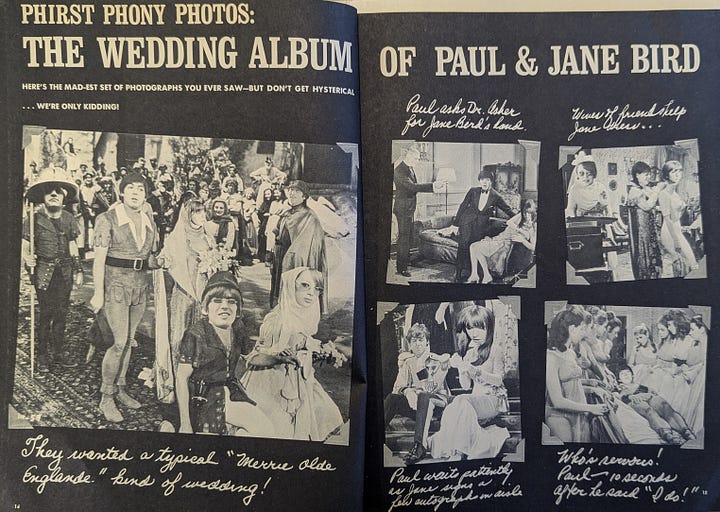

The archive contained a significant number of articles in magazines of the time that speculated on Paul’s not yet having married Jane Asher, and his stated reluctance to marry in general. Here are a couple—

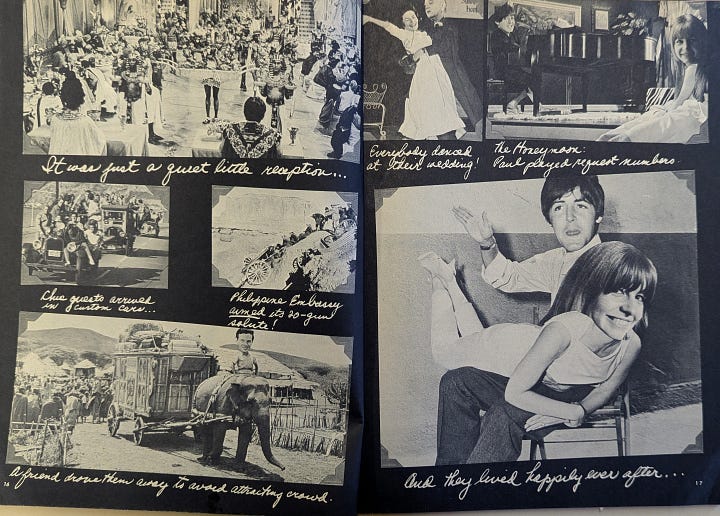

So feverish did this speculation become that someone at Datebook took matters into their own hands—

(Again, click on the individual images to see the full… whatever this is. But don’t say I didn’t warn you.)

And with that… whatever it is… I’m off to London, Liverpool (and Luxembourg).

Until next week.

Peace, love, and strawberry fields,

Faith 🍓4

Auction catalogues might seem like an odd thing to get excited about. But catalogues are usually the only access scholars have to material in private collections. And the catalogues themselves are hard to come by, because they’re usually regarded as either a niche interest or as disposable marketing material, and thus tend not to be formally archived — which is why it matters that Northwestern has an extensive collection of Beatles auction catalogues.

If anyone has links to any of these — especially the Billy Fury romance comics — I’d love to see them. I haven’t had a moment to research them, so I don’t know how easy/hard they are to come by. For sure, they’d be useful for Part Two.

This quote, “reinventing music every six months,” isn’t mine, it’s from an excellent online article I read… somewhere. I will find it and link it here when my brain isn’t drowning in 8,533 photos of archive pieces, but till then I wanted to give credit where credit is due.

There are not enough footnotes in this update. And by that I mean that there are a lot of things I would normally footnote with a source that I didn’t because I’m a bit mentally spent with two weeks of overseas travel still ahead. If there is something in this piece you’d like supporting research for that isn’t there, please e-mail my fab research assistant Robyn and we’ll get you the source.