Hi everyone,

This week, it’s back to answering your questions. (And yes, I still have a backlog and probably always will. I promise I’ll do my best to get to all of them eventually.)

Here’s a (streamlined) version of the question—

Do you have anonymous sources? If so, how do you handle the information they give you?

The answer to the first question depends on the definition of “anonymous sources”.

If an “anonymous source” means a source who has given me information with no indication or context as to who they are and how they might know this information, the answer is— no, I have no anonymous sources.

But I suspect that by “anonymous,” what the questioner really means is, do I have sources that I know the identity of, but who are giving me information that’s “off the record” — aka, information I can use only if I don’t share the identity of the source? And the answer to that question is — yes, I do have several sources like that.

These off-the-record sources are not people I’ve intentionally sought out, for reasons we’ll get to shortly. But as the only mainstream Beatles writer seriously exploring the possibility of John and Paul as a romantic couple (for now at least), I’m not a difficult person to find, for those who have information that they want to share. In other words, while I don’t go looking for them, these off-the-record sources sometimes find me.

As for the second question about how I handle information given to me by off-the-record sources, the answer to that question was covered in part in the Research Methodology Rabbit Hole —

In the course of my research, I’ve had people share information with me off the record. While that information has sometimes informed the direction of my research, none of it has been used in this series unless I was able to verify it independently through publicly available sources, and those publicly available sources are what I cite. I’ve also found and been told plenty of gossip, hearsay and rumour about the lovers possibility, some of it dating back to the 50s and ‘60s. None of that appears in this series because gossip and rumour is not what we’re doing here.

The reason I don’t use information from off-the-record sources on The Abbey is simple — doing so would violate both the research standards and the ethical standards I’ve established for The Abbey.

Here, also from the Research Methodology Rabbit Hole, is my research standard—

All the research cited in Beautiful Possibility is from publicly available material and from primary sources, verified by tracing the research back to the original source of publication.

And—

Basically what I mean by a primary source is that if someone said something, it has to be sourced at the original place where they said it — whether that’s an interview, a conversation, or a piece of their own writing. If something happened, the account of that event has to be sourced to someone who was there when it happened.

When I say verified at the original source, I mean pretty much this: if I can’t trace the quote or the information back to where it first came from — the first person who said it in the first place it was said, or to an account from someone who lived through the events firsthand, it doesn’t make the cut for Beautiful Possibility.

An off-the-record source would meet the “primary source” part of that research standard, assuming they were present when the events they’re describing happened.

As for the “publicly available” part, for our purposes here, what I mean when I say “publicly available’ is that the information must have been originally intended to be shared publicly — in other words, there was an expectation on the part of the person involved that the information would be made public.

So, for example, the Northwestern Beatles archive contains unpublished handwritten notes from interviews with Paul and Linda McCartney. Those interview notes weren’t published, per se, but they were written during an interview in which Paul and Linda (presumably) knew they were speaking to a journalist who intended to publish a story based on that interview. The information in those handwritten notes is, then, “publicly available” in that it’s information that was intended to be made public, even if it ultimately didn’t appear in the finished article.

Also, those interview notes are publicly available to qualified researchers who are willing to invest the time and resources to access the archives. That, too, makes those notes public — but again, only because Paul and Linda were speaking on the record in the interview the notes originated from.

An off-the-record source can rarely, if ever, meet the “publicly available” part of my research standard. First, because I can’t cite the original source of the information. And second, because the information wasn’t (generally) intended to be made public.

For example, if an off-the-record source were to tell me about a private conversation they had with Paul McCartney, the reasonable assumption would be that (absent information to the contrary) Paul did not intend for that conversation to be made public. And thus that’s not information I could ethically use on The Abbey, no matter how credible or valuable that information might be.1

And since I wouldn’t be able to publicly cite the source of the information. I’d have to say, “someone told me X, but I can’t say who, so you’ll have to trust that X comes from a credible source.”

This is, obviously, not how we do things on The Abbey. Given the overall carelessness with which research tends to be handled in Beatles studies (both mainstream and countercultural), no one should believe any scholar who can’t (or won’t) show you exactly where and from who their information came from — and this is, of course, especially true when dealing with a subject as sensitive as the lovers possibility.

All of this is why almost all of the research used in Part One of Beautiful Possibility comes directly from Paul and John — from on-the-record interviews that are (and are obviously intended to be) public, and from their music, because they’ve both explicitly told us that their music is where we should look for the truth of their story.

It’s also why, unlike most Beatles writers, I generally don’t seek out interviews with sources who knew John and Paul. I’d have to ask questions that aren’t mine to ask, in an attempt to obtain information that’s not theirs to tell, because John and Paul presumably never intended for that information to be shared with the world.

These guidelines got me safely (so far at least ) through Part One. But this all gets significantly trickier, when we set out to re-tell the story of The Beatles — and especially John and Paul — in Parts Two and Three of Beautiful Possibility.

For example, what do I do with the private letters between Stu Sutcliffe and Astrid that I’ve accessed in the archives of the Museum of Liverpool? Or what about John’s Dakota recordings, or the answering machine tapes that include Yoko and John’s voicemail messages that are also in the Northwestern archive? Does it make a difference if the information was never intended to be public, but already is because someone before me has made it so? Does it make a difference if that someone is in a position to grant that access — Stu’s mother, for example? Does the standard change when the person in question has been dead since 1967? What about when the person in question has been dead since 1980? Is it different if the information itself is beautiful and life-affirming or… less beautiful?

These are just some of the difficult questions, with lots of shades of grey, that I’m weighing as I research and write Part Two. All are legitimate questions for anyone writing about The Beatles, but they’re especially weighted and consequential when writing about the lovers possibility.

All of that said, even if the information can’t be cited in a published piece of work, off-the-record sources can still be valuable.

As I mentioned in the Research Rabbit Hole, if I’ve been given information from an off-the-record source that I think might be credible — meaning the source is who they say they are and they are/were in a position to know what they claim to know — I do sometimes use that information as a research guide, aka an arrow pointing in a possible direction. I can then follow that arrow to see if it leads anywhere — meaning is there credible, publicly available research to support the claim? If there is, it’s the publicly available research I’ll cite, not the off-the-record source.

In this way, off-the-record sources (as well as anonymous sources) can be valuable as waymarkers. But here’s the thing — they aren’t essential.

As I hope you’ve started to see in Part One of Beautiful Possibility, there is a significant — and even overwhelming — body of research in the public record to support the credibility of the lovers possibility. So much so that if it were any other topic, it would already be part of the accepted narrative. And in Part Two, we’ll continue to do the work of considering that research, when we attempt to re-tell the story of The Beatles through the frame of John and Paul as a romantic couple.

Until next week.

Peace, love, and strawberry fields,

Faith 🍓

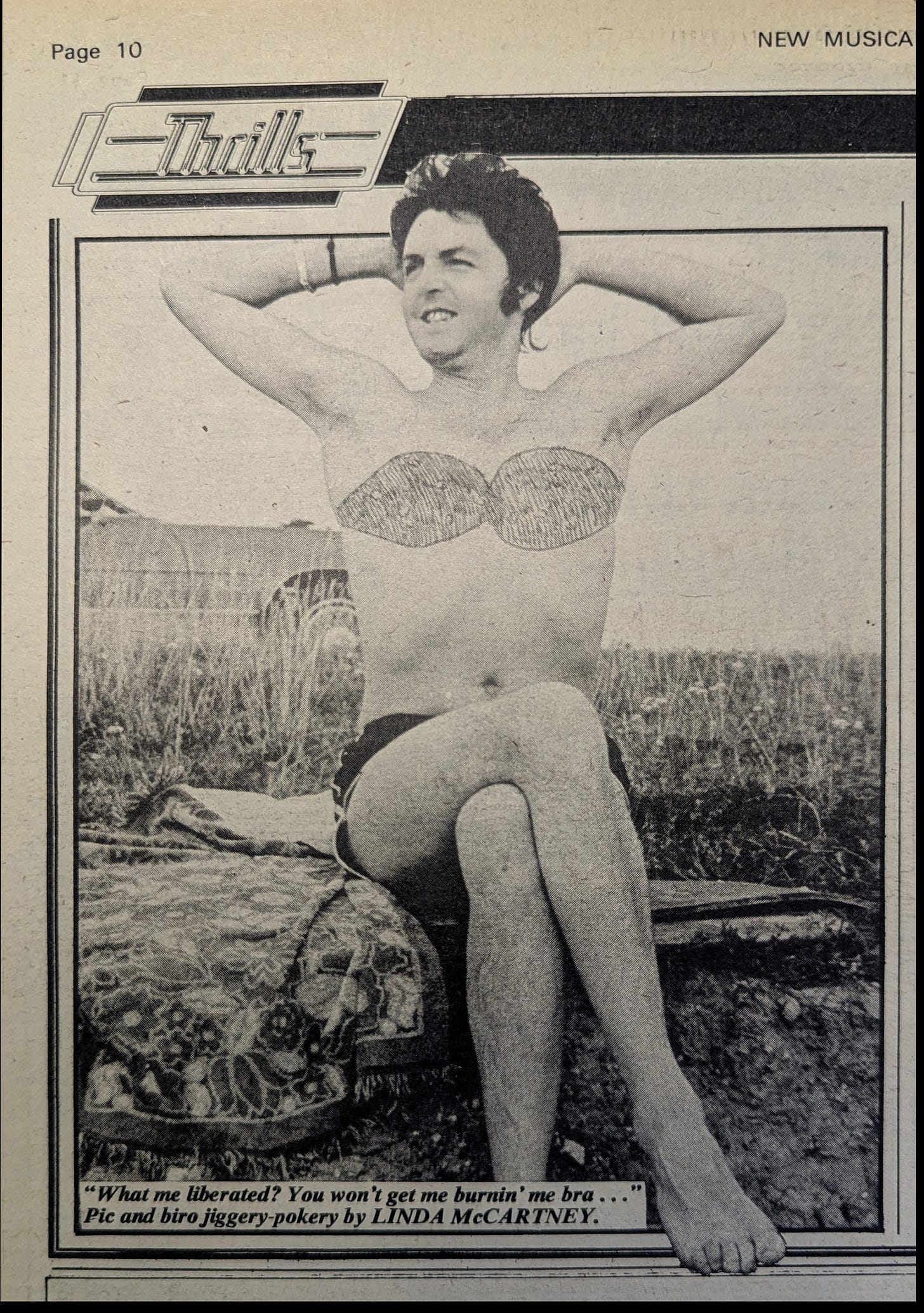

PS This update was a little egg-heady, so for your entertainment, here’s a publicly-available, primary source photo of Paul McCartney in a coconut bra, published in NME, July 5, 1975. Photo and “biro jiggery-pokery” (aka doodling) by Linda McCartney.

Observant readers/listeners might remember that I did, in fact, quote from a private conversation in Part One of Beautiful Possibility, when I quoted what Paul told journalist Hunter Davies in what was intended by Paul to be a private phone conversation (and which Davies subsequently published in a tabloid article and as an addendum to his Beatles biography)

I struggled with whether or not to quote this material in Beautiful Possibility, because this phone call was off-the-record and appears to have been shared with Hunter Davies primarily in his capacity as an old friend, not a journalist, and Davies published it without Paul’s consent. I chose to include the information because it’s similar to what Paul has shared so many times in actual interviews, and because Paul was specifically telling Hunter Davies that he wished that information was public, and so it’s a safe assumption Paul has no objection to that part of his phone call being shared (even if Davies did share it in a most uncharitable and underhanded way).