Happy 2026, everyone,

As most of you know, I stay away from the public discussion of Beautiful Possibility outside of The Abbey, mostly because I’m easly distractable and easily influenced by feedback (good and otherwise), and I need to avoid both of these things so I can stay focused on researching and writing the work itself. And since I lack both the bandwidth and the temperament to do any sort of self-promotion, I rely on all of you to share Beautiful Possibility with the wider world (and a huge thank you to those of you who are doing that. ❤️).

I’m aware, though, that sharing Beautiful Possibility can sometimes be a bit of a challenge, because people tend to prejudge the lovers possibility based on what they think is true rather than on the actual research.

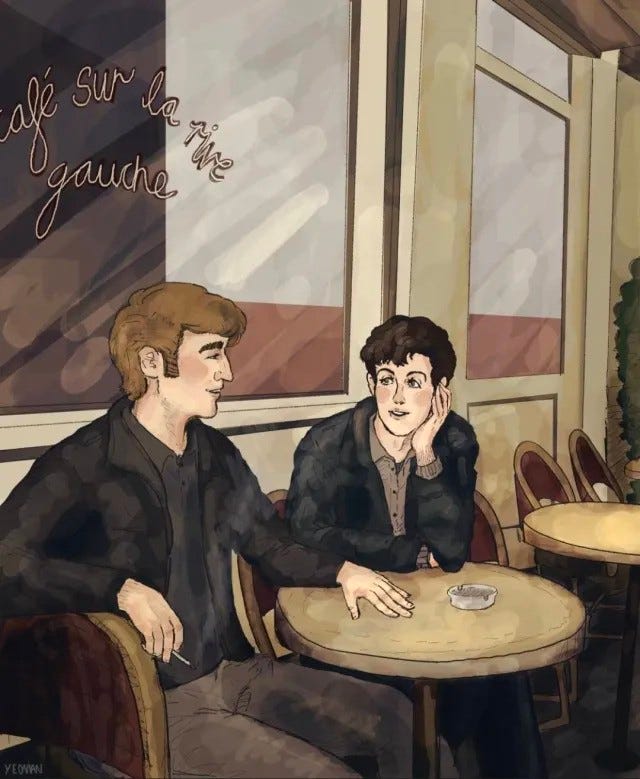

Recently, one supporter of Beautiful Possibility mentioned to me that when he’s looking to persuade people of the credibility of the lovers possibility, he reaches for what he calls “the Paris excerpt.” This is the section from episode 1:4 “Are You Afraid Or Is It True?” that steps through much of the research related to John and Paul’s 1961 trip to Paris.

So to make it easier for those of you who are doing the invaluable work of sharing Beautiful Possibility with the often-sceptical wider world, I thought I’d lift the Paris excerpt out of the episode to make it more easily shareable. It works pretty well on its own, and this way, you have a single “this is the Paris excerpt” link to share when you’re engaging with people online about the lovers possibility.

With that said, then —

The Paris Excerpt

excerpted from 1:4 Are You Afraid Or Is It True

Before we move on to talking specifically about the credibility of the lovers possibility, there’s a caveat, and a big one — because one of the challenges here is that while there’s a substantial body of research to support it, most of the individual data points can be explained in some alternate non-lovers possibility way, if you’re motivated to do so and if you aren’t aware of the full scope of the research surrounding that data point.

So for example, I could tell you that in 1961, John and Paul took a trip to Paris, just the two of them, in honour of John’s twenty-first birthday. And while that might raise an eyebrow, you’d probably say, that’s interesting, but it doesn’t prove anything about the lovers possibility, and you’d be right about that.

Best friends do sometimes take trips together, just like Paul and George used to hitchhike places, just the two of them. Maybe John and Paul just wanted to go to Paris — you certainly don’t have to be lovers to enjoy visiting the City of Love. And maybe John took Paul because John had never been out of the UK before and he didn’t want to go on his own and he couldn’t take his then-girlfriend Cynthia because in 1961, no respectable middle-class Liverpool parent would let their young, unmarried daughter go to Paris alone with her boyfriend — especially if her boyfriend is John Lennon.

All those things are valid, and if you’re looking for a reason to discredit the lovers possibility, it’s easy to look at the Paris trip in isolation and simply choose the alternative explanation.

But individual data points can’t be considered in isolation, when they’re part of a larger story. And when we put the Paris trip in its full context, we get a very different picture.

When you also know that it wasn’t a mutual decision, but rather John inviting Paul to come with him to Paris, and that John paid for almost everything, and that they stayed there together for almost two weeks, just the two of them, in a little hotel in Montmartre—

—And when you know that John and Paul returned to Paris in 1964 on The Beatles’ first international tour at the beginning of global Beatlemania, and that they stayed in a luxury suite at the George V Hotel, which is as posh as it sounds, and that it was there that, in beautiful synchronicity, they learned that “I Want To Hold Your Hand” — a song about a longing to hold hands, presumably in public — had reached number one in the US, meaning they’d made it to the toppermost of the poppermost together, and that multiple people who were on tour with them, including George Harrison, have written about how John and Paul spent an unusual amount of time alone in their suite in Paris to the point that it became a problem,4 and that staying in that posh hotel, Paul to this day recalls thinking of their first Paris trip, staying in a cheap hotel with only a hundred pounds in their pocket.5 And when you know that when they at last emerged from their self-imposed seclusion in their posh 1964 hotel suite, they’d written the song “Can’t Buy Me Love”1 —

And when you know that a decade later, Linda McCartney asked John if he missed living in the UK, and John’s answer was, “I miss Paris,”2 and in a separate interview, said he loved Paris because of how people could be so openly affectionate and romantic, kissing and holding hands in public, and when you know that same-sex love was legal in France in 1961, so two boys could hold hands and kiss and show affection in public the way, if they possibly wanted to, they couldn’t in England3—

And when you know that in the ‘70s, John wrote a story about his memories of meeting his lover in Paris for a secret rendezvous4 and that there’s a home recording of John in the late ‘70s singing a parody of an old French love song in which he calls Paul’s name and riffs about his romantic memories of Paris and a “cafe on the Left Bank,”5 and when you know that in 1978 Paul wrote and recorded a song titled “Cafe on the Left Bank” inspired by their trip6 —

And when you know that the diary page Paul chose to feature in his Lyrics book and in his Eyes of the Storm exhibition (and I do mean featured, as in displayed in the centre of the room in a glass case) is from that original 1961 Paris trip, on which he and John wrote their names together in various configurations exactly like two teenagers in love, and that in 2007, Paul was interviewed on French television and asked what his idea of heaven was, and his answer was his trip with John to Paris in 19617 —

When you know all of that, the Paris trip starts to take on a different context.

Mainstream Beatles writing doesn’t put those pieces together though — if they even know this research exists. Instead, writers just mention that John and Paul met up with a friend from Hamburg in Paris and that he gave them what became the Beatles haircut — relevant information, to be sure, but it rather misses the larger point.

Whatever else happened between them in Paris, their first trip there together is clearly a significant and cherished part of their relationship story for both of them, and I don’t think it’s because they got their hair cut.

When a shared experience becomes deeply emotionally significant in a relationship, it becomes a shorthand for everything that experience represents about that relationship. And when it then appears in other contexts relative to their history, it carries all of that meaning along with it.

The most iconic example of this, of course, is from Casablanca. In the famous final scene at the airport, Humphrey Bogart’s character tells Ingrid Bergman’s character as she’s about to get on the plane with her husband that, “We’ll always have Paris. We didn’t have... we lost it until you came to Casablanca. We got it back last night.”

When he says “Paris,” Bogart isn’t talking about the city, not directly. He’s referencing their shared emotional experience and memories of Paris — what Paris means to their love affair — and he shorthands all of that to just the name of the city where that experience happened and where those memories were made. And because the experience is so significant to both of them, she instantly knows what he means — and so does the audience.

Paul and John seem to reference Paris in the same way as Bogie and Bergman do in Casablanca.

Just like in Casablanca, Paris is never just Paris when it appears in this story relative to John and Paul — and without understanding that, we miss the significance of those references and what they might tell us about the story, as well as the music that was being written at the same time.

For example, events like John “honeymooning down by the Seine” with Yoko in 1969, as he wrote in “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” and then asking Paul to help him record the song, become far more emotionally complex when we know that Paris is always more than just Paris between the two of them.

Without understanding the collection of experiences and emotional associations that’s referenced every time Paris appears in the story relative to John and Paul, I don’t think it’s possible to understand the meaning of that trip, or the meaning of “Can’t Buy Me Love” or “Ballad of John and Yoko,” or John taking Yoko to Paris,8 or John’s feelings about living in New York, or a host of other significant parts of the story. Without an awareness of the lovers possibility, the fuller context and meaning of those events remains invisible, and out of reach.

And without being sensitive to romantic and emotional subtext, you can’t put those pieces together. Paris becomes just a story about a haircut.

I’ve occasionally heard people protest that the problem with the lovers possibility is that it makes a complex relationship too simple. Putting aside that this isn’t in and of itself a reason to discount it — just because we don’t like what something does to a story doesn’t mean it’s not true — the Paris trip is an example of how it’s the other way around. It’s by stripping the lovers possibility out of the story that we oversimplify it — and miss the more beautiful story.

When we focus only on individual pieces of information without doing the work of putting together the whole puzzle in its broader context, we miss the bigger, more complete and complex — and more beautiful story. And this is why it’s difficult to present supporting research for the lovers possibility, because most of that research requires context to be fully understood.

THE FULL EPISODE (including the audio version) IS HERE:

And all of the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here:

https://www.beatlesabbey.com/p/beautiful-possibility.

And here is a graphic if you’d like to use it to share—

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, Liveright, 2022.

also— “John and Paul also wrote “One and One Is Two” in their hotel suite in Paris in 1964.” (Michael Braun, Love Me Do! The Beatles’ Progress, Graymalkin Media, 1964.

“After a late lunch, Linda launched into a long paean to the joys of living in England. When she was finished, she turned to John and said “Don’t you miss England?” “Frankly”, John replied, “I miss Paris.”

May Pang, Loving John, Warner Books, 1983.

“When I first went to Paris aged about twenty-one – well, actually it was twenty-one in Paris, but – the thing was, was all the kissing and the holding that was going on in Paris. It was so romantic, just to be there and see them, even though I was twenty-one and sort of not romantic [thing]. I really loved it, the way the people would just stand under the tree kissing. And they weren’t mauling each other, they were just kissing.”

John Lennon (audio), in The Lost Lennon Tapes, Episode 45, aired November 28, 1988.

(John and Paul returned again to Paris in 1966, but that trip is complicated and requires more context. John also went to Paris in 1969 with Yoko on their honeymoon — but it’s the 1961 trip with Paul that he associates with his love of Paris.)

John Lennon, “The Importance of Being Erstwhile,” Skywriting by Word of Mouth, Harper & Row, 1986, p. 171-6.

There is a lot we could say about the Paris story in Skywriting, but most of it requires context we don’t have yet, so we’ll wait until we get to Paris in the next part of the series to look at it more closely. But I’ll mention here that it contains references to amyl nitrate (google “poppers”), “light in the loafers,” the George V Hotel where John and Paul stayed in 1964, and “God Only Knows,” a song that Paul has named as a favourite and about which there is a whole other story that we’ll get to when we get to the episode about their songs. “There was an underlying bastard to their relationship,” John concludes near the end of the story. “which was to hold them in good stead in later bouts. Neither of them held each other down. In fact, they took it in turns.”

Audio is from Episode 015 Lost Lennon Tapes.

https://www.theindiemusicarchive.com/Audio/Albums/LostLennonTapes/15.mp3

I’ve had both a native French linguist and a non-native French teacher with over 40 years of experience attempt to translate what John is singing — both said it’s a bastardization of an old French folk song and that John — not being a French speaker — is singing French-sounded gibberish and random words, so they weren’t able to give me a verbatim transcript. If anyone would like to give it a try, please share the results with me if you would.

Note that John says Paul’s name multiple times while singing, and his reference to visiting a “cafe on the Left Bank,” matches Paul’s reference to the same thing in The Lyrics (Liveright, 2022, p. 53) specifically as a memory of the ‘61 Paris trip. Paul’s song “Cafe on the Left Bank” was released in 1978 on the Wings album London Town. It’s not clear when the recording of John was made, but either way, it suggests a much closer relationship in the ‘70s than either of them have described in interviews.

Paul McCartney, The Lyrics, Liveright, 2022 (Cafe on the Left Bank)

“When John and I hitchhiked to Paris in 1961, we went to a café on the Left Bank, and the waitress was older than us – easy, since John was turning twenty-one and I was nearly twenty. She poured us two glasses of vin ordinaire, and we noticed she had hair under her arms, which was shocking: ‘Oh my God, look at that; she’s got hair under her arms!’ The French would do that, but no British – or, as we would later learn, American – girl would be seen dead with hair under her arms. You had to be a real beatnik. It’s such a clear memory for me, so it was in my head when I was setting this scene.”

“French celebrity Antoine de Caunes interviews Sir Paul McCartney,” Canal Plus, 10/22/07.

de Caunes: “There is a very beautiful song on your last album called “The End of the End” where you talk about your own ending. It goes, “it’s the start of a journey to a much better place. You mean, better than England?”

Paul: “It’s basically the start of a journey to France. Or Spain through France, (pauses, smiles) Yeah, that’s what it is. It’s a much better place, Paris.”

John took Cynthia to Paris for their honeymoon, too —but it wasn’t exactly his idea.

“One morning Brian opened his daily newspaper and saw photographs of “Beatles’ wife” Cynthia pushing a baby to the shops in a big Silver Cross pram. Instantly, Brian arranged a delayed honeymoon in Paris for John and Cynthia, and on their return, flew to London for official photographs that would present this happy and ideal family group to the world.”

Tony Bramwell, Magical Mystery Tours: My Life With the Beatles, Thomas Dunne Books, 2005.

NOTE: Bramwell was Brian’s employee and he seems to be speaking from firsthand knowledge here.