Love Among The Ruins: Penny Lane

In retrospect, I should have seen the whole catastrophe coming from the minute I stepped off the bus.

AUDIO VERSION

Hi everyone,

A quick reminder that Beautiful Possibility updates, including bonus material, are posted on the News page. You can find the link in the menu bar above. ⬆️ Post wrap-up questions will be answered there as well. (Email Robyn with questions.)

And now… a new chapter from A Complicated Passion: A Memoir of Pilgrimage. (For this chapter, the audio version is probably a bit more fun.)

“I don’t believe this wood is a world at all. I think it’s just a sort of in-between place.”

Polly looked puzzled. “Don’t you see?” said Digory. “No, do listen. Think of our tunnel under the slates at home. It isn’t a room in any of the houses. In a way, it isn’t really part of any of the houses. But once you’re in the tunnel you can go along it and come out into any of the houses in the row. Mightn’t this wood be the same? — a place that isn’t in any of the worlds, but once you’ve found that place you can get into them all.”

“Well, even if you can—” began Polly, but Digory went on as if he hadn’t heard her.

“And of course that explains everything,” he said. “That’s why it is so quiet and sleepy here. Nothing ever happens here. Like at home. It’s in the houses that people talk, and do things, and have meals. Nothing goes on in the in-between places, behind the walls and above the ceilings and under the floor, or in our own tunnel. But when you come out of our tunnel you may find yourself in any house. I think we can get out of this place into jolly well Anywhere! We don’t need to jump back into the same pool we came up by. Or not just yet.”

“The Wood between the Worlds,” said Polly dreamily. “It sounds rather nice.”

— C.S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew

Penny Lane, Liverpool

January 9, 2023

Things go wrong sometimes, on a pilgrimage.

This is true of any kind of travel, of course, whether it’s the ordinary gremlins of timetable misreads, translation errors and bad directions, or the more formidable gremlins of lost credit cards, transit strikes, and unexpected illness.

But one of the ways pilgrimage is distinct from other kinds of travel is that it’s not meant to go smoothly. If it’s too easy or comfortable, if too much focus is given to smoothing the way, chances are it’s a vacation, not a pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage, like prayer, also tends to be a solitary experience, even if it’s undertaken in the company of others. As pilgrims, we travel less to sightsee and socialize, and more in hopes of encountering a more authentic version of ourselves and a deeper personal connection with the sacred, in whatever way we define that word.

But even in solitude, pilgrims are never quite alone. In addition to the relatively benign gremlins of ordinary travel, pilgrims tend to travel with our personal demons. This isn’t necessarily by choice. It’s just that our personal demons have a habit of coming along as stowaways, whether we invite them or not.

All of which is to say that, in retrospect, I’m not especially surprised at how things turned out on Penny Lane. I should have seen the whole catastrophe coming from the minute I stepped off the bus, and probably even before that. Including the whole... situation... with the tour guide. Not that I took a tour, mind you. Pilgrims and tours are about as incompatible as pilgrims and tourists. It was less a matter of taking a tour and more a matter of—

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The point is, personal demons and pilgrimage are a bit of a forced marriage. And when they combine, well.... for now, let’s just say all of what happened has to do with one of the most persistent demons of pilgrimage — expectations.

Expectations are usually a dangerous thing, and they’re especially dangerous when it comes to pilgrimage. Pilgrimage is about being present. And expecting things to be a certain way tends to get in the way of being present for how they actually are.

But it’s hard not to have expectations, when it comes to Penny Lane, because for me it’s always been “Penny Lane.” First among equals, the effervescent twin sister.... lover... soulmate... of “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Penny Lane” is the first Fab song I fell in love with, the one I hold in my heart as the most Beatle-y of all Beatles songs. If, god forbid, I could only have one, it would — without question — be “Penny Lane.”

So my expectations are high — and dangerously so — as I board the No. 86 bus to Speke via Mossley Hill, the semi-posh neighbourhood in which Penny Lane resides.

The bus lets me off not at the Roundabout, but at an auto repair garage just down from the main interchange. This is the first clue that things will not go according to expectation. Once I’m past the I’m here... I’m really here... this is really the actual, for-real Penny Lane part of things, I'm greeted not by psychedelic whimsy, but by the drab practicality of a suburban interchange on an ordinary (if un-expectedly sunny) January day. There’s a health centre and a thrift shop, a pharmacy and a funeral director, a shop selling dance supplies and a Tesco Express, the requisite off-license,1 and more estate agents and solicitors than seem entirely necessary for a single neighbourhood.

And there, in the middle of the Roundabout, is the Bus Shelter.

I knew, before I even arrived in Liverpool, about the Problem With The Bus Shelter, and by extension, the Problem With Penny Lane. But I couldn't — or, I suppose, wouldn't — wrap my mind around it actually being true. Because how could it possibly be true — in the glossed-up world of Beatles pilgrimage sites and multi-million dollar tourism — that a place so profoundly important to the music of The Beatles would be ... well...

As in the days of the Fabs, the Roundabout itself is still an active bus interchange. But the shelter is no longer much of anything. It’s locked up, silent and empty. And unlike every other Beatles pilgrimage site in Liverpool, even in January, there are no tourists taking selfies, no pilgrims offering presence and devotion, no one paying much attention at all. There’s only me, pressing my face to the dirty, graffitied windows, through which I can see only a construction ladder and the remnants of a renovation project long abandoned and left for dust.

Expectations, meet reality.

I’ve only been on Penny Lane for five minutes, and already my heart hurts. So I do what I usually do when my heart hurts, when I don’t want to feel what I’m feeling — I pretend the problem doesn’t exist. No Bus Shelter and voila! — no pain of unrealised expectations.

Denial firmly in place, I cross the street to the Barbershop, which seems more promising. It still has its candy-striped barber’s pole, though the sign identifies it not as the original “Bioletti's,” but as the “Tony Slavin Ladies and Gentlemens Salon.” (sic)

It's a weekday afternoon, but the shop is closed. So once again, I peer in through a dusty window. Inside are old-fashioned barber’s chairs and faded photos of the Fabs getting their hair cut (elsewhere). It’s a bit better than the Bus Shelter, in that at least it’s still, nominally, a Barbershop. But it looks like it’s been awhile, since anyone’s stopped inside to say hello.

I do my best to ignore another disappointment and turn my attention to the other side of the Roundabout — St. Barnabas Church, where once upon a time, a young Paul McCartney sang in the church choir, probably less for the glory of God and more for the glory of Music, which I suspect amounts to more or less the same thing, especially if you're Paul McCartney.

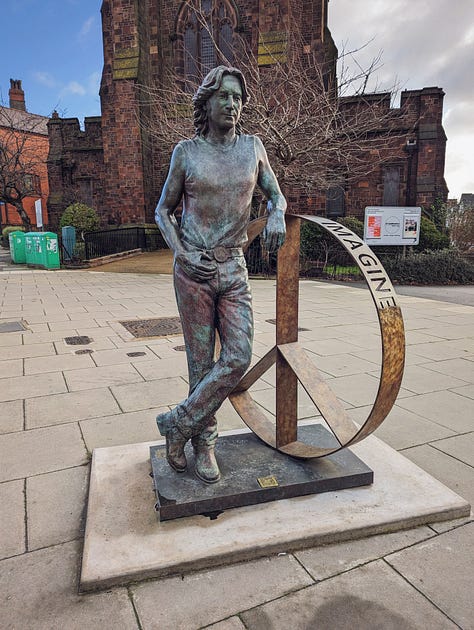

This door, too, is locked. But at least St. Barnabas is still an active church, well-kept and with a marquee announcing times of service. And better than that, the courtyard features a newly-installed bronze statue of John.

It’s a striking and sensitive likeness, even if, oddly, he’s in his post-Fab NYC phase — sleeveless t-shirt and jeans, peering through his iconic round-framed glasses at the middle class practicality surrounding him, maybe wondering how he found himself back here after working so hard to escape.

I linger a few minutes in the connection, incongruous as it seems, before wandering further down the street in search of the Penny Lane sign.

The walk takes me past rows of neatly-kept terrace houses, a print & copy shop, and a few more estate agents 🤔. And — unexpectedly — a pair of red doors and a sign identifying them as the original doors to the Penny Lane Fire Station, which (the sign goes on to explain) was torn down years ago.

The Fire Station doors turn out to be part of the Penny Lane Community Centre. There’s an inner courtyard bounded by a long wall decorated with a psychedelic mural reading “Love Is All You Need” and life-sized portraits of each Beatle, a Yellow Submarine sculpture, and a mosaic of an octopus overseeing a small garden (presumably belonging to the octopus). It's an eclectic-if-scruffy collection, curated and displayed with love and care. And it gives me hope that I might find more inside.

And indeed, inside the community centre, there’s a one-room information centre/gift shop, tiny enough that I can browse while striking up a conversation with the woman behind the counter. Her name is Julie Gornell, and I soon learn that she is — officially — the director of the Penny Lane Development Trust, and — unofficially — the mother protectoress of Penny Lane. It’s Julie who’s responsible for the rescue of the Fire Station doors and the Beatles Courtyard Collection, and, as it turns out, most of anything Fab-related that happens on Penny Lane.

Julie generously offers more of her time than she can probably spare to share with me her years-long quest to turn Penny Lane into a more substantive Beatles pilgrimage destination. We talk for well over an hour — like I said, she’s generous, and more than that, she’s passionate. Her story is a mix of “Penny Lane”-esque optimism and the blunt frustration of a grassroots civic organizer at how difficult it is to get it all going, especially in light of Liverpool’s otherwise strong commitment to the care of its singular musical heritage.

A lot of the trouble with Penny Lane seems to turn on local politics, which are — as always and everywhere — inscrutable to non-locals. There’s a backstory about the Bus Shelter, too, but that’s as murky as the rest of it. Nothing she tells me does much to untangle the mystery of why Penny Lane seems to be the runt of the Liverpool Beatles world, shunted to the side while its sister site, Strawberry Field(s), is pampered and cosseted like a favoured daughter.

More ominously, nothing she tells me does anything to mitigate my creeping feeling that I am not — contrary to expectations — going to find much magick on Penny Lane.

Nonetheless, I thank Julie for her time and her efforts, and continue down the street to the iconic Penny Lane sign. It’s my last hope for finding some kind of magick here — which, I recognise even in the moment, is putting an unreasonable amount of performance pressure on a humble street sign.

The sign is so covered with signatures that it’s virtually illegible. It’s also bolted to the wall and protected by perspex glass — presumably because it contains Paul’s signature from his now-famous Carpool Karaoke appearance, and probably also because nicking the sign has been Penny Lane ‘entertainment’ since the early days. (I have fuzzy memories of one of my hippie parents’ college friends having one on their dorm room wall.)

I’m glad the sign is there, of course. It’d be one more disappointment if it wasn’t. But despite the Signature Of Macca, the Penny Lane sign is — when it comes down to it — just a sign. And more than that — or rather less than that — it’s a sign that points to an ineffable Something that, if it exists at all, I haven’t managed to find, beneath these unexpectedly blue suburban skies.

And with that, it seems I've come to the end of my exploration of Penny Lane. That’s it. That’s what there is.

I walk back up the street to the Roundabout, intending to catch a bus back to the city centre. I feel the same anti-climactic disappointment one might get after fantasising about snogging a passionate crush, only to discover they've got bad breath and they’re just not that into you.

It’s not that this is my first disappointment since arriving in Liverpool. It took most of a morning’s bus ride — clutching a wilting bouquet of flowers — to get to the cemetery where Brian Epstein is buried, only to be thwarted by a locked gate.2 And my interactions with the National Trust, which handles tours of John and Paul’s childhood homes, have been exactly as dehumanizing and frustrating as you might imagine dealing with polite but utterly indifferent (and passionless) British bureaucracy would be, and I’m torn between writing an extended absurdist chapter on the farce of it versus repressing it altogether.

But this is different. Because this is about ”Penny Lane,” the first Fab song I fell in love with, first among equals, the most Beatle-y of all Beatles songs.

To be clear, the problem is not that there’s nothing to do on Penny Lane. There isn’t — unless I’m in the market for dance shoes or real estate. But that’s fine, more or less, because unlike being a tourist, pilgrimage is less about being entertained and more about being present. And in this sense, I suppose all is well, because I’m here.

The problem is that there seems to be — in some way I can’t quite grab hold of — nothing to be present for. There’s no focus, no obvious place to direct attention. And that disrupts the mutual dance that makes pilgrimage what it is. The pilgrim commits to the experience of traveling to a place to acknowledge the importance and sacredness of what happened there. In turn, the keeper of the pilgrimage site enters into a covenant with the pilgrim to offer care and attention to the sacred place, to signal that something important happened that’s worth being present for.

And maybe that’s the deeper problem — that nothing actually happened on Penny Lane, other than Paul and/or John catching a bus to somewhere else. Expectations aside, it’s a bit of a stretch to offer presence and attention to a transit interchange. And this is maybe why Penny Lane struggles in a way that Strawberry Field(s) doesn’t.

Ah... whispers a quiet voice in my head... but what about the song?

I don’t have an answer for that voice, not really. Penny Lane the place feels so far removed from the joyful whimsy of “Penny Lane” the song that it seems impossible to make a meaningful emotional connection between the two.

Nursing my disappointment, I arrive back at the interchange, where in my absence, a grey-haired Scouse tour guide has appeared and is shepherding a small flock of tourists as they selfie in front of the Barbershop.

To say I’m not a “tour person” is an extreme understatement. Being herded around on a prescribed path with a group of strangers listening to a prepared presentation is not my idea of either pilgrimage or entertainment (this is probably the root of my troubles with the National Trust). But my bus isn’t for another ten minutes, and I really don’t want to linger at the Roundabout. So I hover at the edge of the tour group and listen in.

In retrospect, this was probably a bad idea.

For some reason known only to himself, Tour Guy is telling the story of the day John and Paul met. It’s an odd story to tell on Penny Lane, instead of at... oh, I dunno... maybe St. Peter’s Church where, y’know, John and Paul met, and where presumably the tour also stops, because every Beatles tour in Liverpool stops at St. Peter’s Church, because it’s where, y’know, John and Paul met.

That he’s telling the story in an odd place isn’t the problem, though. The problem is that he's—

Well, no— the problem is that I can feel the empty husk of the Bus Shelter lurking behind me like a bandage-wrapped zombie in a ‘50s horror movie and expectations on a pilgrimage are dangerous and I have Penny Lane Disappointment Trauma and my coping mechanisms of choice aren’t working and also I have poor impulse control.

But this is not — in the moment — my perception of the problem. My perception of the problem in the moment is that Tour Guy is telling the story of how John and Paul met, and he’s telling it wrong.

The thing to do in this situation — which I’m certain is as obvious to you as it was(n’t) to me — is, of course, Absolutely Nothing. I mean, I’m not even part of his tour. I’m just a disappointed Beatles pilgrim waiting for the bus.

But for aforementioned reasons, Absolutely Nothing is not what I do. Instead—

“You’re telling it wrong,” I say flatly.

Justifiably startled at the interruption, Tour Guy breaks off his story and turns — along with his entire tour group — to stare at me. I can’t really fault him/them for this, even in the moment. The reasonable part of my brain is staring at me, too, willing myself to shut the fuck up. Not that it helps much.

“The story of the Fête. You’re telling it wrong,” I repeat, because apparently the first time wasn’t inappropriate enough. (Did I mention I have poor impulse control?)

Tour Guy glances nervously at his tour group, which has abandoned their selfies and clustered around us like kids drawn to a schoolyard brawl. I can’t fault them for this, either. Tour Guy vs Disappointed Pilgrim promises to be the best entertainment on-offer on Penny Lane. Certainly better than staring through the window of the closed-up “Tony Slavin Ladies and Gentlemens Salon.” (sic)

“I’ve read all the books,” Tour Guy says, somewhat politely.

“Well, you need to read them again,” I answer, less politely.

This is — in case you haven’t already figured out — not my finest moment.

It's also already a daft argument and it hasn’t even properly started. Re-reading “all the books” wouldn’t help the situation even a little bit. No matter which version of the story Tour Guy chooses to tell — or how many books he reads or re-reads — he’s going to get it wrong, because anyone who tries to tell the story of the Fête as a single, coherent narrative is by definition going to get it wrong because all of the firsthand accounts of the Fête (including John’s and Paul’s) are contradictory — which means I don't know for sure what happened on that day any more than Tour Guy does.

In light of this, it’s not clear what I'm expecting from this situation. But in the absurdist spirit of the song itself, we forge ahead with the argument anyway.

“I think I should know,” Tour Guy answers, also less politely now. “I’m seventy years old and I’ve lived here all my life.”

I'm a bit lost as to what having lived in Liverpool all his life has to do with knowing the actual story of the day John and Paul met. Tour Guy might have been here in 1957, but he wasn’t there — a quick calculation tells me he was three years old on the day of the Fête. And if by some miracle of chronology, he had been there and self-aware enough to know what was happening, it’s a sure bet he’d have led with that piece of information (not to mention written his own contradictory book).

“I don’t care if you’ve lived here for five hundred years. You’re still wrong.” Oh my fucking god, shut up already and let the man get on with his tour.

But it’s far too late for that, because we’re both in it now, the comments section of an online Beatles article come to life (and a reminder of why the comments on The Abbey are disabled). Worse, I have the creeping realisation familiar to anyone who's ever argued in an online comments section that I've started something neither of us has any reasonable, face-saving way to finish.

That same voice of reason in the back of my mind wonders why I’m so vested in this relatively low-stakes “problem” that I'm willing to make my Penny Lane experience more unpleasant than it already is and harass an innocent-if-misinformed tour guide in the process. Does it really matter if a handful of tourists hear a slightly inaccurate version of a story we don't know the truth of anyway?

I consider exit strategies, but evidently Tour Guy is operating from the same demented mindspace as I am, because he, too, does not let it go. Instead, he crosses his arms and glares at me, politeness semi-abandoned, challenge in his eyes—

“A’right, fine then. What do Paul McCartney and Ivan Vaughan have in common?”

I hesitate, thrown by the non-sequitur. “What does that have to do with— “

I stop mid-sentence, because I know exactly what it has to do with. We’ve now devolved into trivia — aka the delusion that obscure factoids about the band’s history are a measure of either authority or devotion.

It’s not that the trivia isn’t important, in its own way. Get enough of the trivia wrong and the truth of the story goes off the rails by the law of cumulative error. It’s just that trivia isn’t the reason to be here, on Penny Lane, in front of The Barbershop, on an unexpectedly sunny day in January.

What I long to say in this moment — what the reasonable voice in my head is begging me to say — is: You grew up in Liverpool in the ‘50s and ‘60s and I am jealous beyond description. Let me buy you coffee... tea... lunch... dinner... a new car... if you’ll tell me everything about what it was like to be here at the same time as John and Paul and George and Ringo. If you’ll please help me find the magick of Penny Lane that’s eluding me.

This is not what I say. Like a suckerfish going for the bait despite knowing it’s going to end with a hook in the mouth, I answer—

“Other than they were in the same class at the Inny? They both have the same birthday. June 18, 1942,” I add before he can ask.

I can’t tell if he’s pleased or disappointed that I know the answer. I can’t tell if I’m pleased or disappointed that I’ve given the answer.

Also to be fair, it’s not actually that trivial a question. And it’s not entirely irrelevant to the story of the Fête. Like so much in this story, the shared birthday is an instance of synchronistic Beatles magick required for everything to happen as it did. Ivan Vaughan was the mutual friend who introduced Paul and John, and Paul says he and Ivan sharing a birthday is what led to their friendship. And without that friendship, it’s unlikely that Ivan would have introduced Paul to John.3

The question isn’t that trivial, but standing on Penny Lane playing street Jeopardy feels trivial, and thus stupid and sad. And I’m already sad (and apparently stupid) enough about Penny Lane as a whole without this... whatever it is. And it doesn’t help that, unlike the rest of my Penny Lane disappointment, this pain is entirely self-inflicted.

Over Tour Guy’s shoulder, I see my bus pull into the Roundabout. This is my chance to put this whole situation out of its misery, but—

“Fine then. What was the original title of Revolver?”

I turn back towards Tour Guy. My bus is right there, I’m steps away from freeing both of us from this trivia hellscape and reclaiming some measure of sanity. But — and yes, I realise how this is going to sound — I stay so as not to be rude. Also, I have the irrational hope that I can redeem this situation — and my dignity — by “winning” the trivia game.

But I’m not going to win the trivia game because—

“There were lots of titles before they settled on Revolver...” I’m hedging because I don’t actually remember the answer to this one. Oh, but— “They sent a telegram with the final title back to EMI from Tokyo, during the first part of the ‘66 tour,” I say, trying for charity points.4 Christ.

“Yes, but what was the first title?” he persists. From the smug look on his face, I know he knows I don't know. Advantage, Tour Guy.

Behind him, the bus pulls away from the Roundabout.

“I don’t recall, but—”

He smirks. I sigh, frustrated and annoyed with my missed bus, Tour Guy, myself, and even the tour group, some of whom are now videoing the exchange on their phones, presumably to be shared to the interwebs with a snarky remark about the insanity of Beatle people.

They would not be wrong. This whole situation is off its head. I remind myself again that I started it. The (new) problem is that I don't quite know how to finish it.

Except, of course, that I do.

“Look, I’m not a trivia person and I don't remember the original title of Revolver,” I say, doing what (other than Absolutely Nothing) I should have done in the first place. I hand him a card with my contact info. “But I am a Beatles scholar and I do have some newer information about John and Paul’s first meeting that you might be interested in.”

At last (sings a choir of angels from on high) the adult has arrived in my brain. But it’s too little too late. Milk’s been sailed, ships have spilled. If there was any magick to be experienced in the encounter with Tour Guy, my handling of the situation has killed it dead.

Tour Guy takes the card, scowls, and — without even glancing at it — shoves it in his pocket on its way to the dustbin. We exchange tense goodbyes.

It’s half an hour till the next bus, so I wander back down past the Roundabout, unsettled and at a loose end for how to spend thirty more minutes on Penny Lane without making things worse than they already are.

Across from the dance supply stop is a hipster tea house. On the door is a graphic of the Fabs crossing Abbey Road.

Beggars, choosers. I'll take it.

I order an Earl Grey and a scone and choose a table by the window, staring out the window at the people that come and go, and try very hard not to beat myself up over my ill-considered encounter with Tour Guy.

It’s an uncomfortable bit of introspection. By confronting him as I did, I have — for the first time — crossed the line from pilgrim into something more akin to an entitled tourist complaining on Trip Advisor that the British don’t know how to make a decent burger.5

I know, of course, that none of my bad behaviour was about Tour Guy at all, but about the disappointment of an experience from which I expected so much. And despite my considerable capacity for denial, it’s no small task to get past that disappointment. “Penny Lane” (the song) looms far too large in the Beatles legend — and in my emotional connection to their music — to make it possible to ignore what’s (not) happening here.

Clearly, this particular pain isn’t going to go away by ignoring it. So I stress-nibble my scone and force myself into an extended stare-down with the Bus Shelter, just visible through the window.

But I am not and never have been good at “sitting with the pain.”

Instead, I deploy my second-favourite coping mechanism — Trying To Solve The Problem. Ever a devotee of The Grand Gesture, I indulge in a series of heroic rescue fantasies — imagining myself as some sort of crusading angel, the Saviour of Penny Lane, swooping in to make everything instantly all better.

First, I flirt with writing an exposé of the local political situation that’s mucking all of this up. But I reject the idea almost immediately. I’m not that kind of writer, and non-locals aren’t in any way qualified to write exposés on local politics. Nor do I want my relationship to Liverpool or Penny Lane to be rooted in that kind of hard and hostile perspective. And more than all of that, I don’t really want to know the sordid details (back to my denial again). I’m too afraid of what I might find. Greed, maybe. Or worse, indifference.

My next idea is that I could buy the Bus Shelter and/or the Barbershop myself, and transform them into what they need to be. I imagine taking my place alongside Julie as a Penny Lane Protectress, reigning benevolently over two beautifully restored Beatles pilgrimage sites — the toast of Liverpool.

It's a heady thought — for all of half a minute. But ultimately it’s an even worse idea than the first one, and not just because I don’t have that kind of money laying around. Given my encounter with Tour Guy and my overall aversion to interacting with the world of Beatles tourism (there's a reason I'm here in January), I’m perhaps not the best person to be the keeper of a physical Beatles pilgrimage site.

The ideas grow sillier and more extreme, and I reject all of them on the basis of sheer delusional implausibility. Out of ideas, my second-best coping mechanism sputters to a stop. I’m left with nothing but a neglected cup of Earl Grey, a picked-over scone, and the thing I most want to avoid — the pain of my unrealised expectations.

Pain goes hand-in-hand with passion — and especially this passion. There’s no way to engage honestly with the story of The Beatles without encountering serious punch-to-the-gut pain — it’s indelibly woven into the narrative. But I didn’t expect pain on Penny Lane, so I didn’t prepare for it. Pain is an anomaly in this otherwise shimmering city of Beatle magick. Liverpool is before most everything about this story that hurts. Before India. Before the breakup and the toxic ‘John vs Paul’ narrative. Before that December night in 1980 and its aftermath.

It’s almost time for the next bus. I politely clear my table — because when I’m not arguing with tour guides, I tend to be inordinately polite on pilgrimage — and step back outside. Across the way, John gazes steadily at me through his National Health glasses, as if to say, well, what did you expect? This kind of shite is why I left, innit?

He’s right, of course. Expectations are dangerous, especially when it comes to pilgrimage.

That first visit was over three years ago. And every time I’m in Liverpool, I return to Penny Lane, with the hope that if things aren’t getting better, they’re at least not getting worse.

On the ‘better’ side, there’s a new mural on the front of the Penny Lane Community Centre — a two-story black and white painting of Paul and John, inspired by Astrid Kirchherr’s iconic photographs at the Field of the Holy Spirit in Hamburg. And of course, the mural is there because of Julie, still engaged in her own labour of love to keep Penny Lane alive.

And then there’s the ‘worse.’ Last time I was on Penny Lane, the Barbershop was closed for real — even the barber chairs and the photographs were gone. And three years on, the Bus Shelter is the same — empty and silent, a temple abandoned to urban neglect and decay. Every time I ride the No. 86 bus to Penny Lane, I hold my breath, afraid the Bus Shelter will be gone, too — torn down and replaced with something square. Maybe an estate agent’s office.

And still, I keep returning to Penny Lane. It’s the expectation that won’t... quite... die.

Sometimes I sit and have tea. Sometimes I walk down to the Community Center. Sometimes I don’t get further than the Roundabout, where I press my hands to the dirty glass of the Bus Shelter as if I could heal it with a pilgrim’s touch. One Sunday morning, I attend the service at St. Barnabas, just to see the brass plaque marking where Paul used to sing in the choir.

But never once have I found the magick I long for. Never once have I caught the faintest echo of a piccolo trumpet or the lingering scent of poppies on the wind.

I've been working on this chapter, on and off, for a year and a half — which, even for me, is a very long time. Some of that is because, as many of you know all too well, I really do write very slowly. Some of it is because of Beautiful Possibility. But most of it is because I keep searching for a happy ending and not finding one. And I’m stubborn enough to keep searching, because for me, it’s always been “Penny Lane,” the first Fab song I fell in love with, first among equals, the most Beatle-y of all Beatles songs.

I don’t have a happy ending to offer, not exactly. I don’t have a justification or a solution for the neglect of the Bus Shelter and the Barbershop, or for the indifference-bordering-on-contempt that the Liverpool Beatles community seems to have for Penny Lane.

But I think I’ve at least managed to make some sense of why I struggle to find the magick on Penny Lane. And it has to do with the nature of pilgrimage, and with the song itself, and with Paul and John and the quality of memory. And most of all — as with everything in this story that matters — it has to do with love.

Pilgrimage is, first and foremost, about being present in a place where something meaningful happened. That’s why we go, so we can be there.

We go to St. Peter’s Church Hall because it's where John and Paul first met. We go to Forthlin Road and Mendips in part because it’s where they wrote their first songs, and to the Cavern because it’s where they performed those songs. We go to Strawberry Field(s) because of the song, yes, but also because it’s where John (and later John and Paul together) snuck over the wall to hide from the world and dream dreams of the Toppermost.

But Penny Lane is not St. Peter’s or Forthlin Road or Mendips or the Cavern. It’s not even Strawberry Field(s). Penny Lane is separate unto itself, a misfit island in the midst of Pepperland — because nothing actually happened there, other than Paul and John, separately and together, waiting for a bus. And by that standard, there are a lot of Penny Lanes in Liverpool — even if they’re not quite as charmingly named.6

But of course, what makes Penny Lane unique — what makes it part of the story at all — is that Paul chose to write a song about it.7 And it’s “Penny Lane” the song — and the circumstances of its composition — that complicates my relationship with Penny Lane the place.

Penny Lane was, and still is, mostly a place to wait for the bus. Unless you’re in the market for dance supplies or an estate agent, there’s not much else to do on Penny Lane — now or then — except wait for the bus. And that makes Penny Lane problematic, when it comes to pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage is about being present. But we’re rarely present when we’re waiting for the bus, because there’s not much to be present for. Trapped between where we’ve been and where we’re going, there’s nothing to do but wait. Our reality becomes distorted, detached. Time stretches itself into unnatural lengths. One minute feels like ten minutes, ten minutes feel like an hour. Lost in our own thoughts, the people around us come and go, characters in a dream. Like the narrator in “Penny Lane,” we don’t know the backstories. We know only what we see.

This is the world Paul sketches for us in his song — it’s the memories of a teenaged poet stuck in a place-between-places with nothing to do but people watch. We see a banker arrive in a motorcar, but we don’t know his story. Why do the children laugh at him? Why doesn’t he wear a mac? Why does the fireman carry an hourglass? Why is he rushing into the barbershop? Like Paul, we don’t know enough to know. We’re just waiting for the bus. Without context, it’s all so very strange.

The “Penny Lane” in the song — the Penny Lane I’m searching for — only exists in Paul’s ears and in his eyes. It’s real, but only in the geography of Paul’s memories.

And more than that, in the geography of Paul’s memories, Penny Lane maps itself mostly onto Paul’s memories of John.

In his 2022 memoir, The Lyrics, the first thing Paul tells us about “Penny Lane” is this —

“When I was going to John’s house in Liverpool, I would change buses at the Penny Lane roundabout, where Church Road meets Smithdown Road. As well as being a bus terminal, and a place that featured very much in my life and in John’s life – we would often meet there – it was near St Barnabas Church, where I was a choirboy.”8

When Paul and John meet up on Penny Lane, they’re teenagers, in the first intoxicating flush of their discovery of one another. And in the first flush of new love, everything — even an otherwise ordinary suburban bus interchange — feels brighter, more colourful, more alive. Photographs of haircuts become works of art. Street peddlers become fairy tale figures. Even the tedium of waiting for the bus becomes an experience of electric anticipation — heralded by the fanfare of trumpets — when we’re reuniting with the one we love.

I suspect this is the deeper — and paradoxically more beautiful — reason that Penny Lane struggles as a pilgrimage site. Falling in love transforms an ordinary suburban interchange into a whimsical fantasyland — but that transformation is only visible to the two people in love. It’s in the ears and the eyes of Paul and John, and in the love they share between them. It’s not accessible via a simple trip to Liverpool, or a ride on the No. 86 bus.

None of this justifies the neglect of the Bus Shelter or the Barbershop or Penny Lane in general. Whatever the complexities of local politics, surely there’s something that could be done, even if it’s just hiring the same person who painted the murals at the Penny Lane Community Center to turn the exterior of the Bus Shelter into a psychedelic homage to the song. Something, anything to show that it’s not forgotten. Something, anything, that shows someone somewhere is paying attention.

But all of that aside, Penny Lane is a reminder that however rich the experience of physical pilgrimage, we don’t need to travel any ‘where’ to be present for this story — because while pilgrimage is about place, this story isn’t and never has been about place. It’s always been about the music, and about the love at the heart of that music. And while the magick of “Penny Lane” isn’t reachable via a trip on the No. 86 bus, it’s always reachable, to anyone any ‘where’ any time —because the magick of “Penny Lane” isn’t in the place, it’s in the song.

You maybe haven’t thought of it as such, but at its heart, “Penny Lane” is a love song — one of Paul’s most joyful love songs, which is maybe why I experience it as the most Beatle-y of all Beatles songs. It’s a love song from Paul to John, and from Paul to Penny Lane itself, the place-between-places that connected Paul and John in their earliest days together, when all that separated them was a bus transfer at the Roundabout.

So today — right now, in fact — I invite you to make your own pilgrimage to Penny Lane. It won’t take long — just three minutes exactly. I invite you to stop what you’re doing — if you’re already reading this, that means there’s probably nothing else in your life you need to do for the next three minutes — and to be fully present for “Penny Lane.” Not as background noise or distraction, not as part of a playlist, not while you're doing six other things, but now and with the full attention of your heart.

For the next three minutes, I invite you to be present to the memories of a teenage boy newly in love and eager to reunite with his beloved in the magickal place-between-places that is — and always will be, no matter how much the City of Liverpool continues to fuck it up — “Penny Lane.”

Or if you don’t have Spotify, here it is on YouTube: Penny Lane

Peace, love and strawberry fields,

Faith ❤️

More excerpts from A Complicated Passion: A Memoir of Pilgrimage—

The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall

Knee-Tremblers & Mystery Cults: The Cavern

Filth and Longing at the Crossroads: Hamburg

You can find all of the episodes of Beautiful Possibility, referenced in this chapter, here.

An “off-license” is a store that sells alcohol to take “off” premises.

Some people climb the walls to get to Brian’s grave. I didn’t and if you go to Liverpool, I hope you won’t, either. Please don’t be that person.

tbf, they almost certainly would have met anyway — the Liverpool rock-and-roll world was tight-knit and deeply interconnected, and genius tends to find genius. But it wouldn't have been nearly the fairy tale beginning that the meeting at the Fête is.

I’m just recounting the conversation here. I don’t know if this is correct, because the stories about the origin of the title are, like most things about this story, inconsistent. So don’t quote me on it — this isn’t that kind of piece. Also for the record, according to Paul in Many Years From Now, the original title was Abracadabra.

They don't, though. Order any other kind of foreign food in Britain and there’s a decent chance they’ll nail it. But if any Brit anywhere ever promises you an authentic American burger, you’d better run for your life if you can.

And Penny Lane is charmingly named despite rumours to the contrary. One of the stories Julie related to me during our time together was that the misinformation (including, among other places, in a footnote in Lewisohn’s “Tune In”) that Penny Lane was named after a slave trader almost resulted in an ill-considered, reactionary and heartbreaking name change. Putting aside the complicated ethics of those sorts of situations, which are not in the scope of The Abbey’s mission, the Penny Lane Development Trust did the careful research required to set the record straight — thus protecting Penny Lane in this crucial way.

This is yet another example of how biographers not being careful with this story does real and tangible harm.

“Penny Lane was primarily written by Paul, so for the sake of simplicity, I’m calling it a Paul song in this chapter. But as we talked about in detail in the Beautiful Possibility Rabbit Hole on The ‘Entangled Form’ of Lennon/McCartney, all Lennon/McCartney songs are in an important way co-written, regardless of the individual contributions of Paul and John.

Lest this tidbit furthers the “John/hard vs. Paul/soft” fallacy that we talked about at length in Beautiful Possibility, now’s a good time to remind you that John, too, was a choirboy — at St. Peter’s Church.