All the episodes of Beautiful Possibility in sequence are here.

This is the wrap-up, so obviously it assumes that you’ve read/listened to all of Part One.

We are broken things, amongst other broken things. We are imperfect and characterised by our capacity to fuck things up, yet still we can move incrementally towards the greater good. This serves as grounds for both self-forgiveness and hope, and reflects our inherent human loveliness.”1 — Nick Cave

Hi everyone,

Well, we made it to the wrap-up of Part One without the world ending, which — given the central theme of this series and the overall state of the world — is no small thing.

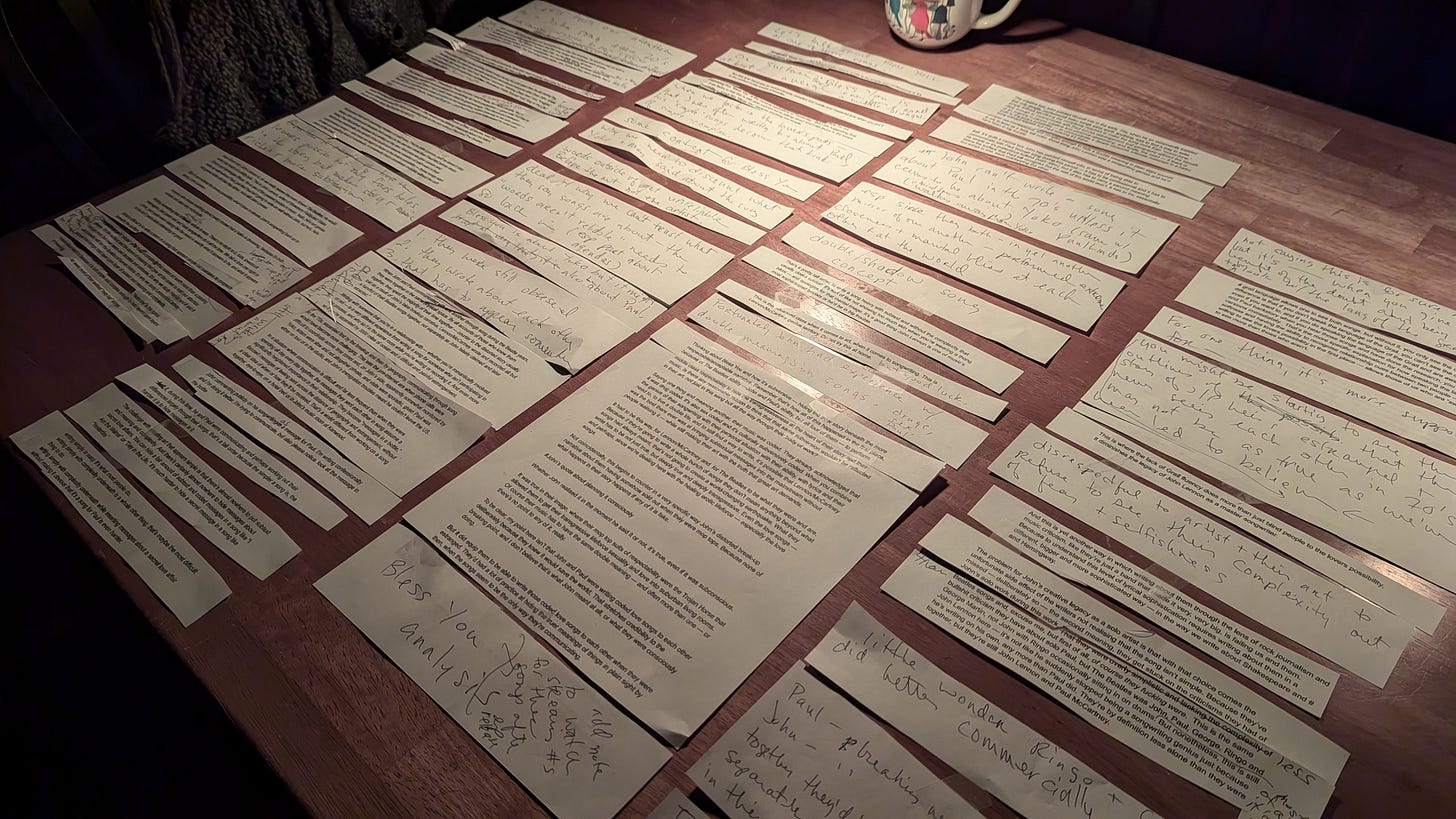

And my dear readers, I don’t know about you, but after those last few episodes, I’m just about poetical-ed out. If I have to write “wound at the heart of our world” even one more time, I may break a washboard over my own head. Also, I’m pretty exhausted at this point. So I hope you don’t mind that this is even scruffier than the scruffiest Rabbit Hole, and also that we drop the lyrical formalities and just chat, like we did in the preface — except that now we maybe know each other a bit better than we did then.

In this wrap-up, we’re first going to talk through the questions y’all sent in, then we’ll talk about the future of The Abbey and Beautiful Possibility and what happens next. And of course, there are also people to thank along the way, because even though it’s my voice you hear and read, many people helped bring Beautiful Possibility into the world — whether they realised it or not.2 😎

We have a lot of questions to cover, so let’s jump right in and get started.

One person wrote in with a collection of related questions—

“Who do you think should be the intended audience for Beautiful Possibility? What is the dream aspiration for the audience scope and size of Beautiful Possibility? How do you see your work influencing the legacy of The Beatles? Is the dream to become a mainstream voice yourself, in the story of the Beatles?”

Let’s start with the underlying frame of this collection of questions — that The Abbey is a countercultural voice. Because whether The Abbey is mainstream or countercultural depends on how we’re defining those words.

I’m guessing that the notion of The Abbey as a countercultural voice is based on the way it directly challenges the orthodoxy of the distorted narrative created and propped up by the writers who still control the mainstream conversation — which is a traditional definition of “countercultural.”

But as I’ve mentioned a couple of times before, I’m not actually part of the Beatles studies counterculture. The Abbey is a mainstream voice in that it’s published on a public, mainstream platform rather than in the Beatles studies counterculture. It’s also a mainstream voice in that I began my public life as a Beatles scholar writing for a well-known mainstream Beatles website. And most of the initial readership of The Abbey was made up of people who read that mainstream website and followed me to Substack (and thank you to all of you who did follow me over here, because y’all are basically the founding members of The Abbey, and I appreciate all of you — especially given you likely didn’t know where all of this was headed when you signed on).

More importantly, though, relative to whether The Abbey is mainstream or countercultural — given that love was the central message of both The Beatles and the Sixties, is it really “countercultural” to write about The Beatles and the Sixties from the perspective of love?

Because if that’s the case, then it seems to me we have it exactly backwards.

The actual countercultural — and I might add, revisionist — voices in all of this are not those of us who experience the story of The Beatles as a love story. The actual countercultural/revisionist voices are the Grail-phobic writers who have allowed their fear and self-interest to distort the narrative away from its original and truer message of love and towards anger and divisiveness — which is about as “counter” to everything The Beatles and the Sixties stand for as it’s possible to get. In this way, the Grail-phobic writers are in reality the faux mainstream, rather than the actual mainstream.

So to answer your question, The Abbey is not only a mainstream voice, it’s far more mainstream than most of the voices who present themselves as such — which gets to your next question about the goals for Beautiful Possibility.

My goal is to offer my skills and time and attention to consigning the distorted, toxic breakup narrative to the dustbin of history and restoring the love to the heart of the story — for its own sake, for the chance to heal the — I guess I am going to say it one more time — wound at the heart of this story and our world. And to fully restore Paul’s right to tell his own story in any way he chooses to.

For me, this is also about restoring integrity — and more than that, care and, again, attention to the way we study and write about The Beatles, and we’ll talk more about that in another answer to another question.

And as I’ve emphasized a couple of times already, I’m also hoping Beautiful Possibility inspires other scholars who are also researching and writing the lovers possibility to publish more openly. And as we’ll get to a bit later in this wrap-up, one such scholar has already emailed to say that she is going to do just that.

And I also hope that Beautiful Possibility inspires us to stop feeling we have to whisper about the love at the heart of this story. And maybe that it inspires those who already are publishing openly to feel comfortable talking about the lovers possibility without euphemism.

This is how the lovers possibility — not the certainty, but the possibility — can become an accepted part of the mainstream conversation.

And that’s my answer to the question about audience and reach. For the narrative to change and for Paul to be free to tell his story — if he has a story to tell — an awareness of the credibility of the lovers possibility needs to reach as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, because practically speaking, we don’t have infinite time to get this done.

Which brings us to the challenge with all of this — or rather another challenge with all of this.

Because while I feel well set up to do my part in restoring the love to the story by writing Beautiful Possibility, I’m also probably not the best person to take the material presented in this series into the broader world, beyond publishing it on The Abbey. And that’s why rescuing the story from the distorted narrative needs to be a group effort, or nothing is likely to change.

I enjoy public speaking and always have, and I have no problem presenting my work in a formal, controlled setting. But I’m extremely conflict-averse, and I’m not good at being articulate under pressure when it’s something I care deeply about. My temperament isn’t suited to the give-and-take of informal debate, and I’m even less suited to the rough-and-rumble dialogue on social media, which is why I’m not on social media at all.

For me to be able to formulate my thoughts, I need quiet and empty space and lots of unstructured time. And when I do share my thoughts beyond my writing, it needs to be with someone who’s genuinely curious and who is first and foremost seeking to understand, rather than simply looking for an argument. And unfortunately, in our “might makes right” world, argument seems to be the only kind of communication most people are looking for these days.

It’s a bit more than that, too. And I’m not sure if this is maybe TMI, but here goes anyway—

For me to connect with this story in the way I need to connect with it to do this work demands an intense, sustained level of emotional openness and vulnerability beyond anything I’ve done in the past. And that’s especially challenging for me because, like Paul, I have a difficult time sharing my innermost thoughts, even in my writing.

My need for that kind of sustained emotional receptivity to both the intense love and also the intense pain in this story means that I can’t at the same time maintain the thick skin required to engage in the give-and-take of dialoguing about all of this in the wider world. Metaphorically speaking, at this point I’m not only thin-skinned, I’m virtually skinless. I bruise easily, when I bump up against the sharp edges of the way The Beatles are talked about in the wider world. And that bruising, which is painful in and of itself, compromises my ability to do the actual work, in the same way that it’s hard for most of us to do any meaningful work when dealing with pain.

Even with the boundaries I’ve set up to protect myself from the hard edges of the world, I still frequently need to step away because of the effect that the pain in this story — and more than that, the distorted narrative and the brute force with which that narrative is presented — has on me. And the more I bruise, the more I have to step away and the slower the work goes.

So practically speaking, I can participate in the larger conversation in real-time, or I can write Beautiful Possibility — but probably not both. And I think I have more to contribute by writing this series than I do dialoguing online, which isn’t something I’m all that good at or find particularly enjoyable anyway.

All of this is why I retreated to the deep woods of Maine to write Beautiful Possibility. And it’s why it’s so important that those of you who feel connected with Beautiful Possibility and who understand the importance of rescuing the story from the distorted narrative continue to share Beautiful Possibility in places where it can reach more of the mainstream world — places where I’m not going to be able to share it, and where it needs to go, to do what it’s intended to do.

This is a good place to stop and say thank you to all of you for opening your minds and hearts to this work, for being patient while it took so long to release it into the world, and for everything you’re already doing and will continue to do to share Beautiful Possibility with the wider world that I’ve mostly retreated from. Without all of you, I’d be writing for the bears and the raccoons, who as far as I can tell, seem less interested in the lovers possibility than one might hope.

Before we move on, there’s one more thing I want to say in answer to the question about who the audience is for Beautiful Possibility — and it relates to an important part of all of this that I don’t think I made as clear as I wish I had in the first part of the series.

Throughout Beautiful Possibility, I’ve done my best to choose my words carefully. And I try to be especially careful never to exaggerate anything for any reason, including for dramatic effect. That said, foundational mythology deals with big things — that’s its nature and why it is what it is and has the power it does to shape our world and our individual lives.

So when I say that everyone in the world is — to this very day — wounded by the breakup of The Beatles and the collapse of the Love Revolution, I'm not exaggerating for dramatic effect. And I’m not referring only to people who lived through the Sixties — which I did not — or to those of us who are especially connected to the story of The Beatles. I’m really and truly talking about every single one of us, regardless of age, geography, gender or musical preference.

Part of what the questioner wrote to me included the following—

“I work a close-open shift at my workplace every Sunday night [to] Monday morning, and Beautiful Possibility makes 4 am on Monday a little more bearable, even something to look forward to.”

This isn’t the only reference to the burden of Mondays that’s come my way, relative to Beautiful Possibility. And that dread of Monday is in and of itself fallout from the breakup and the collapse of the Love Revolution.

And while of course I can’t speak to the specific situation this person is describing, dreading Mondays is what often happens when we’re working a job we’re forced into because of “suffer now, rewards later,” instead of being free to pursue a life of purpose and meaning and joy that the Love Revolution showed us was our birthright.

The Love Revolution — sparked and shaped by The Beatles — taught us that we have the right to be happy in the present moment. And more than that, the Love Revolution taught us that we have the right to shape our lives according to our individual preferences and values, that we have the right to choose our own work, our own beliefs and lifestyle, even when our beliefs and lifestyles go against the mainstream culture.

The Love Revolution permanently changed our definition of a well-lived life — not just for people who lived through the Sixties, but for every single one of us. And this freedom to define our own lives is far and away our most important inheritance from the Sixties.

This right to define our own lives according to our own individuality is a freedom that virtually every single one of us takes for granted today. Every single one of us holds an expectation and a longing for a life defined by our own authenticity — and that expectation holds regardless of our age or background or political beliefs, and whether or not we extend that right to others.

This universally accepted right to individual expression simply did not exist in any widespread way before the Sixties.

Prior to the Love Revolution, only freaks and outliers insisted on a meaningful life defined by their own values instead of by the “suffer now, rewards later” culture. Before the Sixties, it simply wasn’t acceptable to live differently from everyone else.

This is why the Love Revolution was a riverbed-changing earthquake.

The collapse of the Sixties, catastrophic though it was, was not a riverbed-changing earthquake. It did not erase that new expectation of a life based on individual freedom and self-expression — we all still define a well-lived life as a life of meaning and purpose defined by our individual values and preferences.

But the powers-that-be who benefit from “suffer now rewards later” and “might makes right” — and who do not like the new story created by the Love Revolution because it robs them of their power — are making it very difficult for most of us to live that kind of life.

This is why our pain of Mondays is different from the pain of the pre-Sixties world. Our collective pain of Mondays comes from knowing there’s a better way to live, knowing that it’s our birthright to live according to our authentic selves, and being prevented from doing so by the “suffer now, rewards later” and “might makes right” culture that slithered back in when the Sixties collapsed.

There are lots of ways in which this pain manifests itself.

In my experience, one of the most common is as an emptiness. A feeling in the quiet spaces of the in-between that our lives are too small for our longings, that there’s something else, something more authentic, more important, more urgent, that we’re meant to be doing that we’ve somehow forgotten. Or maybe we quite specifically know what that something else is, we just feel like there are too many things preventing us from living it.

The pain of Mondays is found in the ubiquitous quote by poet Mary Oliver — “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

If you’ve ever felt a sense that there’s some more authentic life that’s meant for you that you somehow missed finding, if you’ve ever asked yourself “is this really all there is?” you’re feeling the wounding of the collapse of the Sixties and the breakup of The Beatles.

Of course, there have always been people who felt their lives were missing something — the dreamers, the poets, the rebels who don’t — and can’t bring ourselves to — fit in. But what’s different now is that most people seem to feel that way. And more than that, most people seem to be conscious of feeling that way, and willing to say so.

Beautiful Possibility is for anyone who feels that emptiness, that sense of an unlived life, and who wants to understand and heal it.

So that’s my more complete answer to who the audience is for Beautiful Possibility — and the answer is, in a very real way, every single one of us. Because every single one of us is wounded by the damage done to the story of The Beatles, when it was distorted away from the values of the Love Revolution that has given us this new and better definition of a well-lived life, and back towards the old story of “might makes right” and “suffer now, rewards later.”

I also wish I’d said more to emphasize that — obviously — it’s going to take more than just turning the story of The Beatles back towards love to fix that pain. It would be delusional and naive to suggest otherwise.

Embracing the collaborative partnership of ‘John and Paul’ rather than the false and divisive narrative of ‘John vs Paul’ might have been enough when the Love Revolution hung in the balance in 1970. But it’s not going to be enough today.

What I am suggesting, as a predictive mythologist, is that trying to heal a culture that flows through the riverbed of a broken mythological story results in pretty much what it’s resulted in — a lot of trying to swim against the current, making incremental gains and then losing ground again, in an endless and ultimately ineffective cycle.

That’s what happens when we try to create sustainable change in a culture with a broken foundational mythology. Change is exponentially more difficult than it would otherwise be. And that change will virtually always be temporary.

This is why it’s essential that we pull the foundational story of our culture away from competition, anger, fear and greed, and back towards the only thing that’s ever actually changed the world sustainably for the better — love, not just as a feeling or a social media meme, but as an intentional act, expressed not in outrage and self-righteousness and clenched fists, but in music and art and joy.

This isn’t naive and sentimental optimism. It’s based on proven and observable strategy — because in two thousand years, intentional love expressed as music and art and joy is the only thing that’s ever been effective against “might makes right” and “suffer now, rewards later.”

Again, this is not an exaggeration for dramatic effect. Changing the outcome of a situation by working with the underlying mythological story at play is what I’ve done professionally — and successfully — for many years, for clients who expect tangible results, not poetic exaggeration. It’s what pays for my house and my laptop and my trips to Liverpool.

Having said that, I also want to make more clear that the mythological implications of healing the story are separate from the more individual and specific — and even more urgent — imperative to clear the way for Paul to tell his story — if he has a story to tell — without fear of accusations of revisionism.

As some of you may have figured out, the tricky thing about Beautiful Possibility — even just in terms of describing it to other people — is that there are two separate storylines happening at the same time. There's the “heal the wound at the heart of our world” mythological aspect. And then there's the more personal “clear the way for Paul to tell his story by showing that the lovers possibility is credible” aspect. And those two things are related, but separate.

By setting Beautiful Possibility in a mythological frame, it’s not my intention to put the weight of the world onto Paul’s shoulders by suggesting that he’s obligated to tell his story to save the world — or rather to save the world again. Paul — along with John, George, and Ringo— has given us more than enough already, without demanding that he (once again) save us from ourselves.

Restoring Paul’s right to tell his story — if he has a story to tell — is about making right what we helped to put wrong.

What was done to Paul and John — and especially to Paul — as a result of the distorted narrative is an obscene and unconscionable injustice. And we have the power to fix it by acknowledging the credibility of the lovers possibility in the mainstream conversation. That’s a gift we can give to Paul and John, in exchange for everything they’ve given us

And if along the way, we can make the mainstream Beatles world a kinder place, rooted in love — which by their own accounts was the whole point of The Beatles’ music in the first place — that’s a gift for all of us, too.

While we’re on the subject of things I wish I’d said better, and before we move on to the rest of the questions, there’s another important thing I didn’t make clear in Part One.

When John, in his breakup interviews, characterised himself as hard and Paul as soft, that was — as we talked about — almost certainly about John’s creative insecurity about having to stand on his own as a solo artist, when he was afraid he wasn’t good enough to do so. John's characterising of himself as the hard, angry revolutionary was a way to give his music extra weight. And, of course, it was also John falling back on his defence mechanisms that he’d cultivated in childhood, by hiding his vulnerability behind bluster and faux masculinity.

But there’s a bit more happening here, too, and it’s this next part that I failed to make as clear as it needed to be.

When we’re feeling vulnerable and afraid, we tend to project our vulnerabilities away from ourselves and onto others. John’s first two solo albums — Plastic Ono Band and Imagine — are easily his two most personal and confessional albums. On both of them, John is extremely open about his emotional vulnerabilities, so much so that Plastic Ono Band has become an iconic example of raw, searingly honest songwriting. And emotional vulnerability — which is, of course, emotional receptivity — is the very definition of softness.

It seems likely that John felt even more exposed with Plastic Ono Band and Imagine than he had when he revealed himself as literally naked on the Two Virgins album cover. Remember that John had decided he wanted to write those albums with no lyrical or musical flourishes to hide the honesty of what he was revealing about himself. And that meant the songs on Plastic Ono Band and Imagine exposed his inner pain and heartache — and softness — to the world in an extraordinarily explicit, stripped down, haiku-like way. As he intended, there was nowhere for John to hide in those songs.

Revealing our innermost selves to the world would be terrifying for most of us. And certainly it would have been terrifying for John, given his insecurities and his fear of rejection and abandonment — especially in the midst of his breakup with The Beatles and his estrangement from Paul.

So it’s likely that in order to deflect from his own creative nakedness, and in an attempt to avoid revealing his own fear, he projected the softness in his own solo work onto Paul — whose solo work was equally revealing and soft. John then did to Paul what he was afraid that the world would do to him, by mocking that softness and diminishing its power.

John’s characterising of himself as hard and Paul as soft was — paradoxically — both an act of self-defence and an act of self-sabotage. It’s exactly the sort of thing we do when we’re afraid of rejection and ridicule — we reject and ridicule someone else for doing what we ourselves are doing and feeling. It was basically John saying, “hey, look over there at how soft Paul’s music is, so you won’t notice how soft my music is and make fun of me for it.” And since John was talking to journalists who were themselves afraid of softness, it worked.

In this way, what started this whole slow-motion tragedy off in the first place, relative to the distorted narrative and ‘John/more vs Paul/less,’ was John’s own fear of his own softness in his solo work, and his fear of being ridiculed for that softness. And maybe to some extent Paul’s fear of softness as well, in his struggle to articulate his feelings outside of his art.

Not stepping through that in detail in episode 1:7 was a major oversight. And I’ve now added this same passage to that episode, where it should have been in the first place.

Okay, on to the next. There were also questions about fan fiction, probably because I mentioned that in addition to writing The Abbey, I also read and write Beatles fiction—

What is your opinion about the subjects of fanfic reading/engaging with your work? What tropes and storylines are included in your fanfiction, as a separate expression from your work on Beautiful Possibility?

Let me say first that I was tempted to skip answering these questions, because — believe it or not — this is one of the most dangerous topics in talking about all of this. People who aren’t part of that community have a very distorted and inaccurate understanding, and thus make distorted and inaccurate judgements, about speculative fiction — especially when it involves real people..

I’m very protective of the Beatles “fanfic” community and don’t at all feel comfortable speaking on its behalf because I’m in no way whatsoever in a position to do that. I don’t think any single person could speak for such an eclectic and diverse community, any more than a single person could speak for the Beatles studies counterculture as a whole, or for the story of The Beatles as a whole.

But let me see if I can answer in a useful way — just me, on my own, with my own perspective, and not speaking in any way at all for anyone else or for that community in general.

I’m guessing that this question is asking for my opinion about a situation in which Paul is reading a piece of speculative fiction — likely erotically-themed and sometimes quite explicit — in which he features as a character. And yes, of course there are some ethical considerations at play in that scenario.

Talking about the ethics of speculative fiction about real people is a longer conversation, but there are a few things we can say here.

First, let’s remember again Paul’s creative direction to Ron Howard that we talked about in the final episode. That suggests that Paul is aware of the discussion of the lovers possibility in the Beatles studies counterculture. And since speculative fiction is a major part of that counterculture, I think it’s at least possible that Paul is aware of — and maybe even occasionally reads — Beatles speculative fiction, and as far as I’m aware, has done nothing to interfere with its creation.

Maybe more important is that there’s nothing happening in the world of Beatles fiction that’s anywhere close to as ethically reprehensible as Robert Christgau and Philip Norman having publicly wished for Paul McCartney's death and still somehow being considered “Beatles authorities.” So it seems to me that we have bigger ethical problems to solve than worrying about spicy John and Paul scenarios in speculative fiction that’s almost entirely based in love.

That said, as with most things related to this story, it’s not as simple as all that.

Not everything that happens in the world of Beatles speculative fiction is healthy, and I’m sometimes uncomfortable with some of it. And for some reason, there seems to be more of the less healthy, more troubling kind recently. I suspect it’s a reflection of the state of the world, because art tends to imitate life.

But even so, I’m not all sure that art benefits from being subjected to ethical considerations in the same way that scholarship does. And actually, I’m fairly sure it doesn’t. And that, too, is a problem in our world today that’s keeping us from creating meaningful change. But again, that’s a bigger conversation for another day. Or maybe for my other substack, The Red Abbess, which we’ll get back to a bit later.

I think there’s value in considering what the uniqueness of Beatles fiction offers that isn’t available anywhere else. Because like mythological stories and fairy tales, speculative fiction is an exercise in “what if.” And when it comes to The Beatles, it, too, heals the story, in a couple of powerful ways.

But before we talk about that, let’s adjust our terms — because I’m not wild about the word “fanfic” as applied to speculative fiction about The Beatles. And I’m also not wild about the word “fan” applied in any way at all relative to The Beatles, although I’ve used both on rare occasion in this series — always reluctantly when it would have been too pretentious and awkward to choose another word.

As we know from the damage done by the distorted narrative, words have the power to do significant and long-lasting harm. And one of the ways we can begin to heal the distorted narrative — and thus our world — is by being more intentional with the words we use relative to this story and how we interact with it. And that might start with thinking twice before using the word “fan” in any context whatsoever relative to The Beatles (and please, for sure, not relative to my work or The Abbey or Beautiful Possibility).

I think the word “fan” — which remember is short for “fanatic” — trivializes the awesome (and I mean that literally) power of this story, in the same way that “hysterical” trivializes the Beatlemania teenagers who understood this story better and more deeply than the critics who used that word to describe them. And I also think that the word “fan” encourages people to continue to treat this story both casually and carelessly, as “just a band that made it very very big.”

Hopefully Beautiful Possibility has shown at least some of you that our enduring and powerful connection to the story and music of The Beatles is so much more profound — and, yes, more sacred — than just a “fandom.” And even saying that word out loud in this context makes me wince.

I’d love to see us grow into a more mature approach to this story that’s more appropriate to what it’s evolved into.

I’d love to see us make the transition from writing about The Beatles as a pop culture phenomenon with a “fandom” to considering them in the way we consider Shakespeare, or the legend of the Grail, as an area of serious and profound cultural, artistic — and spiritual — study.

People who engage with the work of Shakespeare, even those who do so in less formal ways, don’t generally call themselves “fans.” They’re more likely to call themselves “students” or “scholars” of Shakespeare. Given the magnitude of The Beatles’ influence on our world, it’s probably time to make that shift relative to the story and music of The Beatles.

That comparison might sound odd, even after everything we’ve talked about. That feeling of oddness is because we’re not used to sharing a lifetime with art and artists of that stature, and we’re certainly not used to artists of that stature being “pop stars” at the same time. Generally, we tend to think of truly great art and artists as existing only in the distant past, now only found in dusty museums and universities.

But that’s our hangup, it’s not reality.

There were, for example, obviously people who lived at the same time as Shakespeare. And the plays of Shakespeare were, at the time, considered nothing more than popular entertainment.

All of which is to say that when it comes to Beatles fiction, I try — whenever it doesn’t sound too pretentious — to use the term "speculative fiction” or more simply, “Beatles fiction” or “Beatle fic” for short, to avoid the trivializing implications of the term “fanfic.”

This is an important distinction to make, in part to avoid trivializing the story as a whole, and also because the story and music of The Beatles holds a unique place in our culture, and thus so does Beatles fiction.

Like the retellings of the Grail legend, Beatles fiction is a collection of retellings of a powerful mythological story. And that puts Beatles fiction more in the category of mythology and folklore than traditional fanfic — in the same way that the retellings of the Grail legend are a collection of retellings of the mythological story of the Grail. In this way, Beatles fiction forms a unique body of culturally and spiritually significant work.

This is a big part of why I write Beatles fiction. The opportunity to contribute to a living body of folklore surrounding a living, foundational mythological story is extremely rare — it hasn’t happened since the Grail legends of the 1500s. And for a mythologist who is also a wordsmith and a storyteller, it’s an irresistible opportunity.

I doubt most of the writers of Beatles fiction have stopped to notice the importance of their work in quite this way, because most of us haven’t yet wrapped our minds around the singular importance of this story. But whether we’re conscious of it or not, when we’re engaging with The Beatles, we’re engaging not merely with a pop culture story, but also with a mythological story of profound significance.

Also, most — though by no means all — Beatles fiction deals with the lovers possibility. And as such, unlike most real person speculative fiction, it explores a real — and hidden — romantic relationship, whether acted on or not. And that makes Beatles fiction different from the playing with fictional pairings — of real people or otherwise — that happens in traditional fanfic. And as such, Beatles fiction offers unique and valuable opportunities that traditional fanfic, as well as traditional nonfiction writing, doesn’t.

Because Beatles fiction explores the possibility of an actual, hidden romantic relationship, and because that romantic relationship is the heart of a foundational mythological story, Beatles fiction functions in another different way from traditional fanfic — as a collection of healing stories.

Again, this isn’t metaphorical. I’m speaking quite literally — and quite practically.

As I mentioned, doing this work is often emotionally difficult, because it involves engaging with the story consciously and remembering that this is a story about real people who experienced — and in Paul’s case, continue to experience — real pain. And because there is so much sadness and pain in the real story, speculative fiction is a necessary shelter from the storm.

For me — and I’m fairly sure for many others who connect deeply with this story — it’s essential to spend occasional time in a world where the breakup didn’t happen, where John and George are still alive, and where John and Paul get to live happily ever after. And since the question also asked what my favourite themes are, those themes — collectively called “fix-it” fics — certainly top the list.

I’m not sure I’d have made it through the often painful research and writing of Part One without the frequent and life-affirming shelter of Beatles fiction — which is a big part of why I’m both deeply in debt to and fiercely protective of the world of Beatles speculative fiction, and why I try to be very careful not to say or do anything that might cause it any kind of harm.

There’s another benefit, too. It might surprise some of you that speculative fiction — both the writing and reading of it — is an invaluable source of research for the work of writing Beautiful Possibility. And beyond its healing benefits, this is what most interests me as a Beatles scholar.

I don’t want to venture too far into this part of it, because there is enough to say about this subject to merit a full-length Abbey piece someday, if I can figure out how to write it without doing harm, but—

Because Beatles speculative fiction explores the dynamics of an actual relationship that might also have been a real and ongoing love affair, in the hands of a sensitive, Grail-fluent writer, speculative fiction functions like the holodeck in the Star Trek universe.3

Playing out possible scenarios — real and imagined — involving real people and real relationships in speculative fiction frequently reveals complex and often startling psychological and interpersonal insights that simply aren’t available through formal, conventional scholarship.

And here’s a good place to stop and say thank you to the world of speculative Beatles fiction, because many of the most important insights in Beautiful Possibility were sparked by reading an especially perceptive piece of Beatles speculative fiction. And much of what will become Part 2 of Beautiful Possibility began life in what is currently an as-yet-unpublished novel-length piece of speculative fiction I’ve been working on about the early days of the band.

And this, I think, gets to your question about the difference between my writing on The Abbey and my Beatles fiction writing.

In some ways, there is no difference. And to the extent that there is a difference, because of the freedom it allows, speculative fiction — not just by me, but by many of the best writers in that world — is often a more nuanced and accurate articulation of the same ideas we’re talking about in Beautiful Possibility. Sometimes it’s easier to express complicated truths in fiction, just like it’s sometimes easier to express complicated truths in song.

The next question is a bit less elevated, but I bet more of you than just the person who sent in the question are thinking it, so—

If John and Paul were lovers, what about all the girls they supposedly slept with during their Beatles years?

I flirted with doing a Rabbit Hole on the research in support of — or rather the notable absence of credible research in support of — the supposed hotel room “shagfests” that are so much a part of the story as it’s been told over the years.

But I felt that such a Rabbit Hole would border on sensationalism, and also that it strayed a little too close to speculating on sexual orientation — which as we’ve talked about, we're not going to do and don’t need to do in order to establish the credibility of the lovers possibility. And since we didn’t need to debunk the shagfests to establish the credibility of the lovers possibility, I decided against doing so.

But here we are anyway — y’all are determined to get me into hot water, it seems. And I said I’d do my best to answer your questions. So let’s give it a go, and see if we can keep it classy.

The stories of “Satyricon”-style exploits — as John once put it, referencing the ancient Latin novel of sexual decadence4 — make a prominent appearance in virtually every Beatles biography, because of course they do. Not only are the alleged shagfests the ultimate straight male fantasy, but much like “immovable heterosexuality,” they’re so very reassuring to Grail-phobic writers, relative to dismissing the credibility of the lovers possibility.

But they’re only reassuring because Grail-phobic writers conveniently ignore the lack of actual supporting research. And they also ignore that sexuality is complicated, and that it’s possible to be attracted to and to have relationships — including casual sex — with different genders without it defining our sexual orientation, and that who we sleep with, or how often, is frequently unrelated to who we fall in love with and who we have a serious romantic relationship with.

What I’m saying is that even if these supposed “shagfests” did happen, having a lot of casual sex with a lot of women has little to nothing to do with whether or not John and Paul were lovers.

As for the lack of supporting research, we’re for sure not going to go too far down that Rabbit Hole here.

But I will say that ten minutes of searching online for first-person accounts of “my night with John Denver” brings up an entire forum thread of anecdotes (John Denver also having been known for his profligate interest in sex with groupies on tour), whereas multiple prolonged searches by both myself and my fab research assistant Robyn have so far brought up no credible, primary, first-person “my night with a Beatle” stories at all. As in, not a single one.5

Given that there are four Beatles and only one John Denver, that’s a significant disparity. Because while the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence, at the very least it suggests that once again the story as it’s been told doesn’t add up.

There is, again, a lot we could step through about the many reasons why the “shagfests” are probably a wildly implausible piece of speculative fiction all on their own. And we’ll maybe talk more about that when we get there in the story.

For here, I’ll point out that virtually all of the secondhand accounts of erotic hotel room shenanigans with fans come from people — and by people I mean male journalists and biographers — who weren’t there and are just repeating what they’ve heard or read elsewhere, and are likely indulging their own fantasies by retelling those stories.

There are also secondhand accounts that come from people who were part of The Beatles’ entourage and inner circle. And these accounts may be motivated by a more honourable and protective need to obscure and misdirect traces of the lover's possibility in the story — especially given the unusually loyal and tight-knit nature of the Beatles’ inner circle compared to other entourages.

And it’s also worth remembering here that while male pop stars of the time were expected to be unmarried, they were also expected to have a beautiful girl on their arm at social occasions. More than that, not having a beautiful girl on their arm in and of itself tended to lead to gossip — as it still does today.6

And just hypothetically speaking, if there was gossip, in the early ‘60s, about how the two frontmen of a pop band seem to have an unusually close relationship,7 then exaggerated rumours of out-of-control hotel room orgies would be a very good way to tamp down that gossip among the the press and music business insiders (who could, in turn, be counted on in that era not to publicize either side of those rumours).

And I’ll also add here that while I’ve found no specific, credible, first-person accounts of any shagfest-like activity, there is quite a bit of primary research in the years following from people who were on those tours that what the Fabs mostly did in their hotel rooms was play games, watch movies and sleep. That doesn’t mean that’s all that ever happened, of course, but if there were any shagfests, they don’t seem to have been a regular occurrence.8

There’s a lot more research and analysis available on this subject, including a lot more to be said about Brian relative to all of this, and the specifics of why the accounts in some of the memoirs don’t actually add up. And we’ll maybe get to that in part 2. But I think at this point, that’s about all we should say about this topic.

A’right, I hope I answered that question with the requisite respect and discretion. Now on to another question that’s liable to get me in trouble—

Do you think George and Ringo knew about John and Paul?

Well, first, this question — in which I’m going to assume that “knew about John and Paul” refers to a literal romantic relationship between them — presupposes the truth of the lovers possibility. And remember that all we’re doing here is establishing the credibility of the possibility that John and Paul were a romantic couple. And that puts some relatively tight boundaries around answering a question like this. But again, let’s give it a go.

The only truthful answer is that if John and Paul were lovers, then I obviously don’t know if George and Ringo knew because I’ve never spoken to either, and even if I had, it’s unlikely they’d have told me if I’d asked.

But if you're asking me to speculate, as an exercise in “what if,” about whether or not — if there is truth to the lovers possibility — George and Ringo knew, my educated guess is that, yes, they would have had to have known — and probably officially, rather than in that “know but don’t officially Know” kind of way.

As we’ve talked about a little bit — but as we all probably know already — the closeness of not just John and Paul, but the four of them, was essential to their magick. I don't think that closeness could have sustained itself as it did, if that big of a secret had been withheld from half of the band.

And I’m not at all sure a secret like that could have been withheld from George and Ringo. As we’ve seen in the photos and videos of John and Paul together, they were not exactly subtle in their interactions with one another in public, and they were almost certainly far less subtle in private. And since neither George nor Ringo is blind, I doubt it would have been sustainable for John and Paul to keep that secret when it was just the four of them, out of view of the public.

On the other hand, there’s a plausible scenario in which George and Ringo didn’t officially know, but knew in that kind of way where everyone knows and no one says anything about it. And that maybe that was a source of unspoken tension, especially relative to George.

And there’s another plausible scenario in which they didn’t know and were perhaps forced into knowing at a certain point — maybe in India. And maybe that contributed to the way things fell apart — again especially relative to George maybe feeling excluded on a whole other level than he’d perhaps felt previously.9

On a related note, relative to any additional “did so and so know?” type questions, I think it’s wise to be sceptical of scenarios that include more than a very select handful of people knowing about a possible romantic relationship between John and Paul. And this, as much as anything else, might be why they had such a small and tight-knit inner circle, compared to the larger entourages of almost every other pop band.

The more people who know something, the more likely they are to reveal that secret, even accidentally. And there were a lot of mind-altering — and lip-loosening — drugs circulating. And even more social currency in sharing that kind of information. And people in general are not good at keeping secret information that gives them social currency.10

If John and Paul were lovers, that’s more than just a spicy piece of gossip. The potential damage of revealing that secret would have been extreme, at the time when same sex love was illegal and widely condemned in the mainstream culture of both the UK and the US. And that damage would have extended beyond John and Paul to everyone in their circle, including their families.

It’s hard to think that either of them would have been careless enough to risk that damage — which might be another reason why the research supporting the lovers possibility is buried beneath many layers of PR — including, maybe, the alleged and possibly fictional shagfests.

But again all of this is just educated speculation. The only possible true answer to whether or not George and Ringo would have known about an affair between John and Paul is “I don't know.”

Okay, next question, which seems to be from a Beatles countercultural scholar —

I'm curious about why you didn't mention the Montauk outtake when you talked about “(Just Like) Starting Over”?

For those of you unfamiliar with the Montauk outtake, this is is a studio outtake of an improvised verse in “(Just Like) Starting Over,” in which John sings in sexually explicit terms about memories of romantic rendezvous with a lover in “a little place down in Montauk,” while also riffing on The White Album’s “Why Don't We Do It In The Road.”

In addition to the quotation of a ‘Paul song’ title, which as we”ve talked about, seems to be a lyrical tell that John is writing about Paul, with sufficient context, the Montauk outtake definitely adds to the supporting research for the credibility of the lovers possibility.

The Montauk outtake is especially significant because it adds credibility to the possibility that John and Paul were still a romantic couple in the ‘70s and through 1980 — in part because it means we have not one, or even two, but three sets of lyrics (including the final version) that all point to “(Just Like) Starting Over” being written for Paul.

I didn’t mention the Montauk outtake In the Playlist Commentary Rabbit Hole because I only included research in Part One that met a certain set of parameters—

First, that it’s primary research. Second, that the research doesn’t require extensive context to show why it supports the credibility of the lovers possibility. Third, that the research doesn’t speak to either Paul or John’s sexual orientation. And fourth, that the research doesn’t overstep the bounds of ethical speculation by getting inappropriately specific about the private details of a possible love affair between the very real people involved.

The Montauk outtake meets two out of four of those parameters. It is primary research — we have John on tape singing it. And it’s something we could talk about without dealing with sexual orientation.

But the Montauk outtake does get dangerously close to talking about the private details of a possible love affair. And more practically, it also requires a reasonable amount of context to understand why it supports the lovers possibility, beyond what was possible in Part One.

It seems all but certain John’s not singing about Yoko — there’d be no need for a secret hotel rendezvous with his wife. And it’s almost certainly not about May Pang for all kinds of reasons, including that (as we talked about) even May Pang doesn’t think “(Just Like) Starting Over” is about her.

But we’d need a lot more context than we have room for in Part One to fully consider whether John is singing about Paul (although obviously, yes, I think it’s highly likely that he is).

In light of your question, I did go back and footnote the outtake in the Playlist Commentary Rabbit Hole, and here as well, for those of you who want to read it.11 And we’ll talk more about why it supports the credibility of the lovers possibility when we get there in the story — but probably only in general terms.

Okay, next question, which takes us to some safer ground—

I read that Paul called “Yesterday” "Scrambled Eggs" because for some time he didn't have lyrics to the music. He was going around humming or playing it to everyone. So I'm wondering if you have any information or comments on (1) how/when he came up with the lyrics, and (2) why didn't John contribute to the lyrics?

In answer to the first part, Paul has said that he wrote the lyrics for “Yesterday” while driving through the countryside on a vacation in Portugal. And there’s probably no reason to doubt him when he tells that story.

Here is what he has to say about it in The Lyrics (edited for length) —

“During a break in the filming [of Help!], Jane and I went to Portugal for a little holiday and we landed in Lisbon and took a car ride... (sic) and I was in the back of the car, doing nothing. It was very hot and very dusty, and I was sort of half asleep. One of the things I like to do when I’m like that is try to think. ‘'Scrambled eggs, bah, bah, bah . . . (sic)” What can that be?’ I started working through some options. I wanted to keep the melody, so I knew I’d have to fit the syllables of the words around that. ‘Scrambled eggs’ – ‘da-da-da’. You have possibilities like ‘yes-ter-day’ and ‘sud-den-ly’. And I also remember thinking, ‘People like sad songs.’ I remember thinking that even I like sad songs. By the time I got to Albufeira, I’d completed the lyrics”12

As to why John didn’t contribute to the lyrics, that’s probably an issue of place and time, rather than any desire on Paul’s part to exclude John from the creative process — although given John’s reaction that we talked about in our day trip to “Unscrambling Yesterday,” John may have felt otherwise.

The creative process being what it is, songs — like babies — come when they come. Had it been John on that road trip with Paul instead of Jane, the two of them would almost certainly have worked on the song together. But since John wasn’t there, Paul was on his own and in his own head, and that’s where the lyrics presented themselves.

And while John and Paul have both said that they often helped one another finish or polish songs that one or the other had written, the lyrics to “Yesterday” — as we all know — needed no polishing. And John was clearly wise enough and sensitive enough to their artistic merit — and gracious and respectful enough of his creative partner’s talent — to realise that, despite his own creative insecurity.

As for why Paul didn’t ask John for help before the road trip through Portugal, we don’t know for sure whether he did or not. Only Paul knows that. But if Paul didn’t ask John for help, maybe it was because Paul dreamed the melody fully formed, and thus it was a more personal song for him. Paul does seem to have an unusually intense relationship with “Yesterday,” maybe for the reasons we talked about in “Unscrambling Yesterday” — or maybe for reasons he himself isn’t even consciously aware of. And speaking as an artist myself, sometimes work is too personal even to share directly with your most intimate creative partner until it’s finished.

More importantly, remember what we talked about in the Rabbit Hole on the entangled form of Lennon/McCartney.13 In a long term, intimate creative partnership — romantic or not — it becomes impossible to sort out the individual contributions of each partner. And that’s true whether the partners are writing together in the same room, or one of the partners is on a road trip through Portugal and only has the voice of the absent partner in his head.

In this very real way, although “Yesterday” is without question mostly a Paul song, it’s also nonetheless a Lennon/McCartney song — or more accurately, a McCartney/Lennon song — even if John didn’t directly contribute a single word or note or idea. And I suspect on his better days, Paul would be the first to acknowledge that, given how often he’s said that he keeps John’s voice in his head as he writes.

The next question deals with the continuing troubles of Beatles writer Mark Lewisohn that we briefly mentioned in the Research Methodology Rabbit Hole—

"I wonder if it's counterproductive not to use any of the research carried out for Tune In at all? By that I mean: the citations for Tune In are filled with independent primary source material such as newspapers and public records, so I would have thought keeping the book to hand, noting down citations and following the source to that primary material would be very helpful. One could do that while ignoring quote trickery/editorialising in the main text. It just seems a shame to cut off a source of sources, so to speak, when those sources exist independently of the author and whatever biases he has."

And yes, agreed, and I should have been more clear in the Rabbit Hole about the distinction the questioner is making here.

I’m hesitant to say much about the specifics of the Lewisohn problem, because it’s both not my research and also not my primary area of interest or work. So if you have specific questions about Lewisohn’s frankenquotes, I’ll put the link to original research in the footnotes and encourage you to reach out to the authors of that research directly.14

That said, yes, biographies, including Tune In, are absolutely a source of primary research references. And I do occasionally use biographies — including Lewisohn’s — as part of the research process in just the way the question describes.

What I didn’t make clear enough in the Rabbit Hole, when I said I wouldn't cite Lewisohn, is that I was referring to his primary research — the material that he’s gathered from personal interviews. Since we don’t have access to his original audio (assuming he uses audio), there’s nowhere to go to verify that what the person said is actually what they said. And given Lewisohn’s history of manufacturing frankenquotes, we have a heightened reason not to trust that he’s being faithful to what the person actually said, when he quotes his own interviews.

In this way, the problem with Lewisohn's primary research is similar to Sheff, but it’s much more extreme. Instead of gluing together quotes from the same interview like Sheff does — which is bad enough — Lewisohn seems to glue together quotes that are sometimes years apart and that were said in entirely different contexts. 15

And then there’s the bias factor, which as we’ve seen is also not unique to Lewisohn. But because we’re dealing here with the lovers possibility, it matters especially that Lewisohn has gone on record to assert categorically that “John and Paul weren’t lovers.” Not that he doesn’t believe they were, or that he doesn’t think there’s research to support it, but that they weren’t lovers, full stop.16

This assertion on Lewisohn’s part is — there’s really no other good word for this — delusional, because there’s no way he could possibly know for sure, any more than anyone other than John and Paul could. And because he’s so stridently sure about something he couldn't possibly be sure about, and because he would probably prefer not to be wrong about something he’s been so stridently sure about, he’s highly motivated — consciously or otherwise — to alter quotes relative to the relationship between John and Paul to point away from the lovers possibility, just as he shifted the narrative away from the lovers possibility in his description of the Nerk Twins trip that we considered in that Rabbit Hole.

And all of that means that Lewisohn’s primary research is across-the-board unusable — not just relative to the lovers possibility, but overall. Because even beyond his track record of creating frankenquotes, if he’s so dogmatically sure about one thing that he can’t possibly be sure about, what else is he sure about that he couldn't possibly know? And how has his research been distorted to align with those “sureties”?

Again, as we've seen, this bias isn’t unique to Lewisohn. But what makes Lewisohn unique is twofold—

First, it’s the extremity of his quote manufacturing, combined with his flat-out denial of something he can’t possibly be in a position to deny. And that makes him more unreliable as a source than other biographers — which is saying something, relative to all of this.

And second and related, Lewisohn hasn’t earned trust because one of the main ways that a scholar earns trust is by acknowledging that they're not infallible and acknowledging when they've made an error or when they don't know something. And Lewisohn hasn’t, as far as I can tell, done that, either relative to the lovers possibility, or his frankenquotes, or his research in general. In fact, he very much seems to have staked his claim to his supposed “Beatles authority” on his research being flawless — a not-uncommon position for a man to take in a culture that shames a man for being uncertain or for being wrong.

The Greeks have a word for that kind of arrogance. It's called hubris. And we inevitably pay the price when we indulge in hubris.

Which is a good segue to the next question—

Do you think John and Paul were lovers?

I was wondering if someone was going to ask this, and sure ‘nuff, someone did.

And the answer is, yes, of course I do. And more than that, as I was candid about in episode 1:4 in acknowledging my own confirmation bias, I want them to have been lovers, because that possibility is so beautiful it takes my breath away.

But I don’t know for sure that they were lovers, any more than anyone other than John and Paul can know for sure that they weren’t. And absent a very specific kind of supporting research — which to be clear, I do not have and would not share if I did — there’s no reasonable way my opinion can be more than educated and well-researched speculation.

And now is a good time to remind us all once again that nothing about Beautiful Possibility is intended to prove that Paul and John were lovers, only that the possibility is credible.

And also that, as hopefully Beautiful Possibility has shown, opening our minds and hearts to just the possibility — not the certainty — of a romantic relationship between John and Paul is where the magick is. Because in doing so, we restore the lifeforce love to the heart of the story, reveal the hidden complexities and resolve the inconsistencies in the story, and restore Paul’s right to tell his own story — if there is a story to tell. And as many have shared with me over the years, that possibility makes the whole story more complete, more complex, and more beautiful.

Some of you also sent in meta questions. Here’s the first one—

I noticed that you always post at 8:57 am. I'm guessing that's deliberate, do numbers mean something to you?

It is deliberate and thank you for noticing.

While I’m not obsessive about it, it’s hard to be a mythologist and not notice that numbers feature prominently in mythological stories and fairy tales — the numbers three, seven, nine and thirteen in particular.

And numbers feature in the story of The Beatles, too — most notably the number nine, John’s favourite number, and synchronistically, the number of full episodes in Part One of Beautiful Possibility.

And of course, in my time zone, Beautiful Possibility posts at 7:57 am, and July 6, 1957 is the day John met Paul. So that seemed an appropriate time to post new episodes.

Number-observant people might also have spotted that the premier date for Beautiful Possibility was February 24. And 2+2=4 is the mathematical formula of the Fabs. (If only it had been 2024, but I suppose we can’t always have everything.)

Okay, next question.

One of you mentioned that the theme music for Beautiful Possibility is a bit of an earworm.

I can’t tell if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, so I’m not sure whether to apologise or not. But the musical theme of Beautiful Possibility is composed and played by me on my beloved Ibanez Artwood acoustic guitar — the same guitar that has sat unstrung and unused for well over a year while I’ve devoted my attention to finishing Part One of Beautiful Possibility. I hope to give it some attention after Part One wraps — guitars should be played, not stored in a closet, and especially this guitar, which is quite something special.

Also while we’re talking about the music, can I also mention the logo, which was not designed by me, but by fab designer “Daisy B” on, of all places, Fiverr. I didn’t expect much, and I was stunned at what she came up with. I wanted a logo that incorporated the yin/yang idea, relative to hard/soft and the way John and Paul each complimented and had parts of the other in themselves. What she came back with — the intertwining of John’s guitar and Paul’s bass, and the way John’s guitar looks like a crescent moon — exceeded my wildest expectations.

That logo turned out so beautifully that I did consider some Beautiful Possibility swag. But I quickly discarded the idea, because that would involve selling things, which brings us to the next question—

Is there a way to financially support Beautiful Possibility?

I answered this in an earlier episode, but it’s important — and also generous and lovely — so let’s address it again.

Thank you so much for wanting to support Beautiful Possibility in this way. It’s deeply appreciated. But at least for right now and for the foreseeable future, I don't believe it would be ethical to take money for this work. I think it would send the wrong message to Paul in particular, if his love for John was in any way monetized.

Writing Beautiful Possibility is an act of intentional love, pure and simple. And I think it’s important that it be experienced that way by everyone involved, as part of learning to nurture this story instead of consuming it.

So again, the very best way to support this work is to continue to share and talk about Beautiful Possibility with friends — in person, online, wherever you can. Because people are going to need a little help to understand that this series is more than it might seem to be on the surface.

And it’s not just about sharing Beautiful Possibility. Sharing anything at all relative to the credibility of the lovers possibility, or the ways in which the distorted breakup narrative is false — whether it’s my work or someone else’s work or your own thoughts and research — all of it helps. And it helps especially if you share it in the mainstream conversation, because that’s how we, together, restore Paul’s right to tell his own story, and how we restore the love to the story of The Beatles.

And speaking of sharing work, I have a bit of a prezzie for all of you, as they say in Liverpool.

In the Rabbit Hole on Beatlemania, we talked about the police training film of the Beatles 1966 concert in Hamburg that was on the DVD I bought at the Erotic Art Museum off the Reeperbahn.

After reading that Rabbit Hole, literary scholar Hanna Schubert contacted me from Germany and volunteered to translate and subtitle the film. She and her friend Tobi have now finished that project — and a huge thank you to both of them, because their work is a great gift to Beatles scholarship. I think this is the first and only time this film has been translated out of its original German and made available online.

This film is of special interest to me because both Hamburg and the 1966 tour are of particular significance when it comes to the mythological roots of Beatlemania. We’ll talk more about that when we get there in the story. But for now, here’s the link to the video including the English subtitles—

And here’s a link to the transcript, which includes additional footnotes and context.

If you want to read more about either Hamburg or the ‘66 tour, there are two pieces on The Abbey for you. One is the piece on my trip to Hamburg, which we’ll get to later in this wrap-up. And the other is one of the first pieces I wrote as a Beatles scholar, about Revolver and the ‘66 tour.

If you do read the Revolver piece, please keep in mind that it’s written as a lyrical, rather than a scholarly piece, so it’s not footnoted or specifically supported with research. We may look at the same concepts considered in the Revolver piece in a more scholarly way in part 2 of this series.

More importantly, Hanna has given me permission to credit her by name, along with her credentials, to show that, in her words, “there are intelligent, thoughtful people out there who believe in the importance of the lovers possibility.” In this case, Hanna’s credentials include a Bachelor’s Degree in Comparative Literature and English, and a Master of Philosophy degree, with Distinction, in Comparative Literatures and Cultures from Cambridge University.

A big thank you again to Hanna and Tobi for this work. And a thank you to Hanna for taking me up on my appeal to speak up publicly in support of the credibility of the lovers possibility. This is how we heal the story. I hope she’s the first — well, second — of many more.

Okay, next question.

One person wrote in to ask if I had a recommended books list to replace those “Best Books about the Beatles “ lists with all the Grail-phobic books on them.

And yes, I do. I’ll include it in a separate section below this wrap-up, along with some thoughts about each book.

As a general answer, unsurprisingly I encourage you to choose primary sources over biographies, for all the reasons we’ve talked about over the past months. And by “primary sources,” I mean books and interviews by those who were actually there when the events they’re writing about took place.

You will not lack for material, if you stick to primary sources. Everyone who ever breathed the same air as the Fabs seems to have written a book (I just finished a memoir by their hairdresser). I’ve been working my way through primary sources for over three years and still have a ways to go.

Of course, sticking to primary source material doesn’t eliminate bias. There’s no way around the reality that virtually everyone in this story — including the Fabs themselves — has a reason to manipulate the truth in one direction or the other.

But for the most part, the bias in primary sources tends towards the author wanting to make their role in the story out to be more than it was (including the hairdresser). And this is an expected and very human bias that’s relatively easily taken into account and worked around.

What you will not find in the primary source material relative to this story is the distorted breakup narrative — because the distorted breakup narrative was created after-the-fact, and apparently without much consultation with the people directly involved in the actual story. And that alone makes those first-person primary sources far more accurate than any biography written (at least so far) about the Fabs.

Also, most of these primary source books seem to have been completely ignored by Beatles biographers. So unlike the biographies that tend to recycle the same (often distorted) research over and over again, primary source books have some genuinely new material in them (including from the hairdresser).

Okay, next question—

Is there anywhere online you know of where men in specific could discuss the ideas in Beautiful Possibility? I don’t mean the lovers possibility or The Beatles, but the larger ideas about the fear of softness?

I gotta tell you, this question moved me so deeply that I teared up when I read it. And the questioner — whom I assume is a man asking on his own behalf — isn’t the only one who had this question. I saw at least one comment on Substack asking essentially the same thing, but I didn’t have a good answer at the time. So let me see if I can help now.

First, there’s a shadow question contained within this question, because you probably noticed that unlike most projects like this, I haven’t created an online community around Beautiful Possibility. This is for the same reason that I have comments disabled on The Abbey. And I only realised when this question came in that I haven’t yet explained why that is. So I should probably do that first, and then we’ll get to the actual question.

The mission of Beautiful Possibility and The Abbey overall is to change the way we talk about and engage with the story and music of The Beatles. And as we’ve talked about, the most valuable and important part of engaging with this work is to talk about it in the larger world, with people who aren’t yet aware of what we’re talking about here.

If you’re talking about Beautiful Possibility in a community that’s part of The Abbey, that’s a closed circle, because it’s a conversation you’re not having elsewhere, where it could do so much more to heal the story. I’m hoping you’re all going off and talking about the ideas in Beautiful Possibility elsewhere, because that’s what heals the story — and also where it restores Paul’s right to tell his story (if there is a story to tell).

Also, as you may have guessed from what I shared earlier, moderating and leading an online community is not exactly my skillset. I know from tragic attempts to do just this on prior occasions that neither you nor I would be happy with that situation. I just don’t have the temperament for that sort of thing, for the same reason I don’t have the temperament to engage in the give-and-take of online dialogue.

This “talk about it elsewhere” approach works well for discussion of the credibility of the lovers possibility and The Beatles in general — there are already many places online, in the mainstream and the counterculture, to talk about both of those subjects.

Where this approach doesn’t work so well is for a situation like the one the questioner is describing.

I’m aware that much of what we talked about in Part One, with regard to the cultural definitions and traps of masculinity, the fear of softness, and the turning away from the Grail, are deeply personal issues for many of you — and especially for the men who are listening. And I know from talking to my male friends that many men are struggling with the narrow definition of masculinity imposed by the culture, and the damage that it’s done to the world and to their individual lives.

If this series has touched a need in some of you to explore those issues more deeply in the context of Beautiful Possibility, I don’t want to leave you on your own without any kind of community or connection or support — because essentially what this questioner is looking for is support for a Grail quest. And there is probably nothing more urgent and important to our world right now than turning our attention towards the Grail.

So if you are a man in search of other men who have also connected with the larger concepts of masculinity that we’ve talked about in Beautiful Possibility, I have a few things to offer you.

First, I’ll include a list of possible resources beyond Beautiful Possibility at the bottom of the recommended reading list at the bottom of this wrap-up. I can’t speak for the quality of these resources firsthand, but they come from a male friend who is also deeply interested in these issues. It’s highly likely that the men who are engaged with this list of resources would be interested in what we’re talking about here, relative to the fear of softness.

And second, if you want to connect specifically with other men who are listening to Beautiful Possibility, I invite you to email Robyn with your contact information. You can find that email on my personal website at faithcurrent.com.

Robyn and I will then connect those of you who email expressing an interest in talking with other men about Beautiful Possibility with one another, and you can take it from there and set up whatever y’all want to set up to have that conversation. And if there is something I can contribute to that conversation as it unfolds, please let me know and I’ll do my best to help.

If you’re feeling at all awkward about sending such an email, you don’t need to use your own name and you don’t need to provide any other details — this is different from the lovers possibility situation where it really matters that people stop hiding behind anonymity and talk about it in the light of day.

For the non-men among you, please don’t feel excluded by this. Although we all feel the effects of that narrow definition of masculinity, the issues surrounding fear of softness are obviously more personal and difficult for men struggling with masculinity than they are for the rest of us. And our culture has already made it difficult enough for men to be vulnerable — exploring that vulnerability in a group that includes women would probably be next to impossible. So I hope those of you who are not men will graciously allow for the men who are listening to have this opportunity for themselves.

For the rest of you, if you already have an online community in which you’re discussing Beautiful Possibility — whether the larger mythological and psychological/spiritual concepts, or the lovers possibility — I’d be happy to visit your community (virtually or otherwise) for an AMA (Ask Me Anything). Just email Robyn and let her know and we’ll set it up.

I hope that’s helpful. And again, I was deeply moved by this question, and your willingness to ask it. And I’m sorry that I’ve left it until now to address it.

All of which brings me to a question that I have.

And it’s a question for the disciples of the distorted narrative, and more specifically for those writers who hold onto it, who might still be listening and who haven’t yet consciously connected with the message of Beautiful Possibility — because I suspect there are at least a few. And we’ve spent a lot of time in this series talking about these writers, but no time at all talking to them — and that seems like an oversight.

My question is simple, and I invite any of you who are still in thrall to the distorted narrative to give it some serious thought —

Why are you even interested in The Beatles at all?

I’m asking this question — in all gentleness, but also in all seriousness — because you — and again, by “you” here I mean disciples of the distorted narrative — claim to care so much about this story and this music, but you don’t seem to like anything about it.

You don’t like Lennon/McCartney as a collaborative partnership because you don’t seem to like the idea of an equal partnership at all. You don’t like The Beatles as a collaborative band, because you want John to be three-quarters of The Beatles. You don’t like Paul, or his music. And you don’t like John or his music, either, because the John you defend so fiercely is — by his own admission — not even a real person. And his alleged ‘hard’ music that you keep talking about doesn’t actually exist, either.

You're not interested in exploring the possibility that their music has deeper meaning. And despite all four of them having said repeatedly that love is what their music was about, you don’t seem to want anything to do with love, because you do almost nothing other than ridicule love — at least with regard to this story and this music. And more than that, you seem to do everything you possibly can to twist this story and this music away from love.

So I’m left wondering what it is that you do like, that’s actually true, about The Beatles? What is it about this story that keeps you so stubbornly attached to wanting to own and control it?

I’m a bit at a loss as to what you’re getting out of all of this — because if you have to distort a story so far from the actual truth of it that it becomes unrecognisable, in order to personally connect with it, it’s hard to see why you’d care so much about it in the first place.

Now I’m asking these questions as if I don’t get it. But I do get it, or at least I think I do.

I suspect that all of that loud, obnoxious bluster coming from the distorted narrative crowd is the same as John’s loud, obnoxious bluster during his Breakup Tour. That as with John, under all of that fear and pretzel-twisting and lovers possibility denying, even those of you who cling hardest to the distorted narrative are connecting with the love at the heart of this story — because there’s no way to connect with The Beatles in any meaningful way without connecting with the love at the heart of the story.

Because that love, in all of its beautiful complexity, is the story.

And that you haven’t yet worked up the nerve to turn your conscious attention to it, in a culture that shames men out of having the courage to be consciously and openly receptive to love.

And also maybe that our consumerist “might makes right” culture is tricking you into thinking you can love this story by controlling it, rather than letting yourself fall into it and — more importantly — caring for it.

But it doesn’t work that way.